"What am I?" : Intersubjectivity, Social Objectivity, & the Free and Equal Other | Existential Basics 6

a Short Essay for the Modern Existentialist

We are not human by birthright… but instead, because we make each other so.

1 | Intersubjectivity

So, Husserl gives us a concept that we call Intersubjectivity—that is:

The relationship which individual Subjects will form through interaction with one another.

In other words:

Intersubjectivity is the connection between people.

Truth is knowledge that we create, and value that we assign—at least, that’s what we think is true to the best of our knowledge. But, if that really is the case—if our experience is Fundamentally Subjective in nature—then how can it also be true that we, as separate, individual people, can report that we experience a similar reality? If we could all just be brains in vats—if there’s a sense in which no horses are ever real—and if we can never know or confirm with absolute certainty that, when you and I look outside, we actually see the same world… then how can we say with any degree of certainty that you and I exist in a common space?

How can we really say that we know that we inhabit the same world?

…

I think that, maybe, we’ve always thought of ourselves a little too much as individuals. We place too much emphasis on our own personal experience—too much weight on what we ourselves believe and perceive. But you and I; we’ve never been alone. Sure, we’re alone in our experience—in our Subjectivity and our individual conception of the world. But, it’s also equally true that, for our entire lives, we’ve lived in the company of the Other. We reach out for one another—we shape and we mold each other into people. We form connections, and we seek with utter desperation to bridge the gap that we see between the appearance of our reality and the experience of the Other.

When we connect—when we form those bridges—we begin to exchange information and to construct our experiences together. We form a kind of network—and, at that point, we can no longer consider ourselves to be just isolated individuals. After all, we’ve already become a part of a kind of social cloud-consciousness, founded upon a faith and a fiction—a collective Subjectivity. We choose to trust—to believe that the experience of the Other is valid and true, and is thus in turn capable of confirming the validity of our own experience, and of our own world.

We, as individuals, come together to form societies. We create culture and establish law. Together, we forge a kind of social consciousness and a social memory. Our individual experience joins itself with the Other’s in order to form a collective fantasy. This is the nature of our “reality”—our Intersubjectivity, our Facticity, and… our Social Objectivity.

The way in which our aggregate Subjectivity appears to each and every one of us.

2 | Subjective Objectivity: a Different Kind of Dualism

The idea of “Objective truth” is implicitly epistemic in nature. What that means is that:

If you can say that something is real, then that implies that you must first have been able to discover it in reality.

In other words, when we say the phrase “Objective truth”, we can only really be referring to something which is a Social Objectivity—because, after all, it is impossible (at least, to the best of our knowledge) to express as real or to discover as real something which is a Metaphysical Objectivity.

This is what Husserl says:

That in its nature as the aggregate Subjectivity of individuals, Intersubjectivity, itself, is what allows for the formulation of a type of Objectivity—a Social Objectivity, created by means of the collective exercise of individual Agency.

In Sartre’s words, this is what we call Facticity:

The fact of the world, and of the reality which we create together.

Here, we discover a different kind of dualism—not a Cartesian one, with nothing to do with bodies or souls—but instead, a dualism which says this, that:

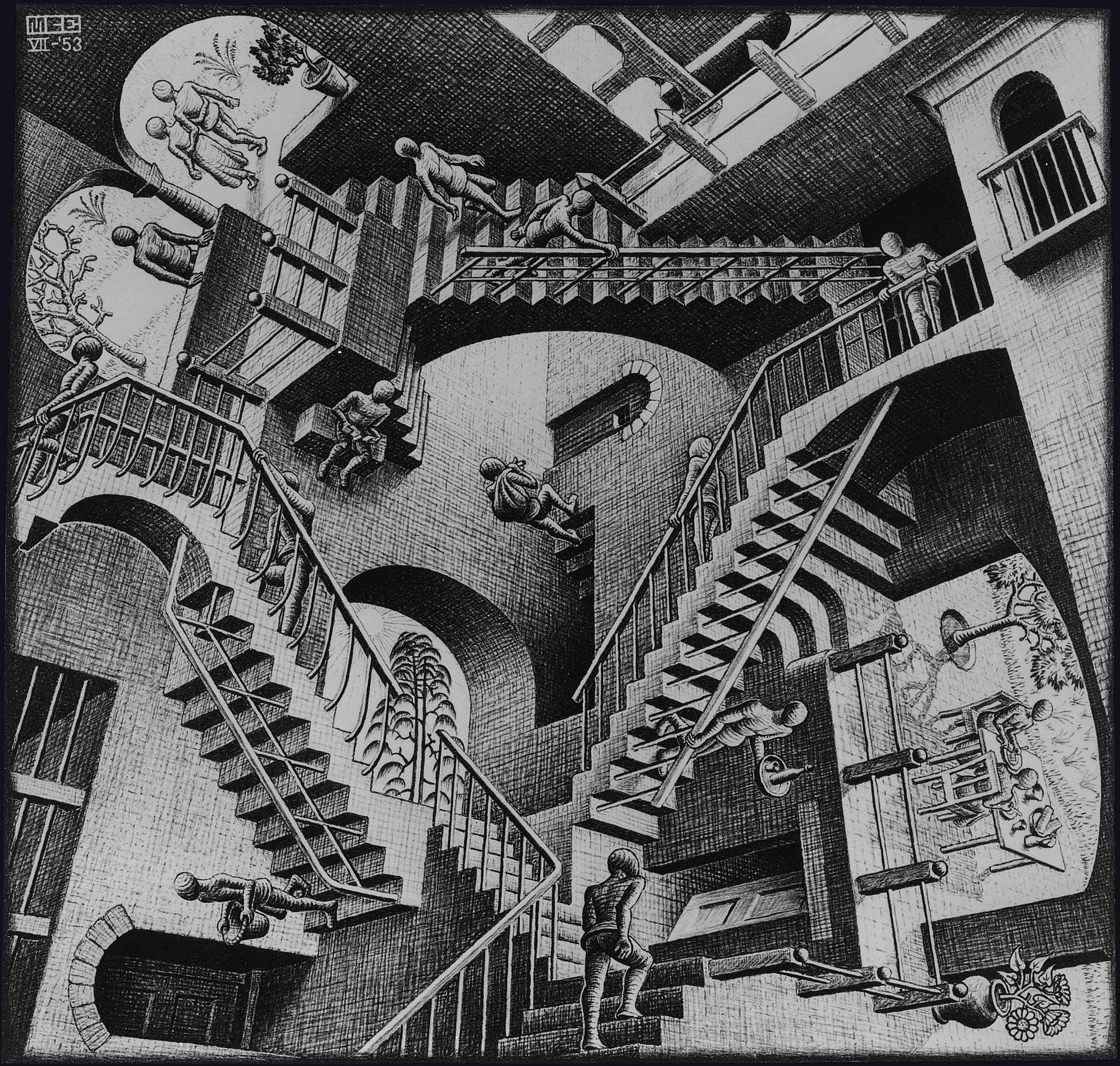

We, as human beings, at once both do and do not occupy a common space of experience.

A dualism… of Subjectivities.

…

We are alone—as brains in a vat, trapped within our own bodies and minds. Yet still, at the same time, we are fundamentally connected to one another—nothing more than just simple aspects of a collective, social cloud-mind.

We are Subjects, which exist and live in a world of Social Objectivity—a kind of Objective world, not because it exists beyond our ability to experience and perceive it, but because it’s the world which appears collectively to us all. It’s not a world of Metaphysical Objectivity—not a world of concrete, absolute truths which we can know with complete certainty. Instead, it’s a world composed of aggregate fiction—of Subjective experience which is shared among the members of an interconnected society.

This social reality—our reality—is indisputably real; not because it can’t be fake in some arcane, metaphysical sense… but instead, because truth is value that we create. Because we believe in the truth we’ve imagined, we therefore have made it real.

Our conception of the reality in which we live is just that—our conception, in which we choose to believe.

3 | The Three Modes of Existence

Man is Subject. Man is Object. But, just as much as he’s at once both of these things, we can see that, empirically, Man must also be the thing which exists in between.

Thus, we can observe that Man exists simultaneously within three different modes of existence:

The first is what we can call Individual Subjectivity—the mode in which Man acts and exists as a conscious, Agentive individual within a world of Objects.

The second is Metaphysical Objectivity—in which we must infer that we exist as absolute Objects and constructs of a world which we cannot perceive, and therefore cannot know.

The third is what we’ve named Social Objectivity—the result of our Intersubjective status, and the mode in which we exist as Objects in the eyes of the Other; as constructs of a physical world which we can and do perceive—

An Objectivity… of a Subjective kind.

4 | Conclusions

Sartre can be a divisive figure, at times. It often seems, after all, to people who are unfamiliar with his philosophy, that when he says that all people must be free-and-equal Agents, he must be advocating for or codifying some kind weird, pseudo-metaphysical system of ethics. What these people fail to realize, however, is that Sartre’s philosophy isn’t a prescriptive one; but instead, that it’s strictly descriptive. In telling us that all people must be free-and-equal Agents, Sartre isn’t trying to say that all people should be treated as though they’re free and equal. What he’s doing, instead, is simply describing a state of reality—that it’s a fact that, in a very real sense, all people are already basically just people.

To make the claim, after all, that this isn’t the case—to deny the human status of the Other—isn’t some kind of moral evil. It’s just simply, factually… empirically wrong.

Or, as Sartre would say…

We, as Subjects, must acknowledge the humanity—the free-and-equal status—of the Other. This is because we’re not only Subject—not the only Agent in the world—and they aren’t only Object; not just things of the world which we act upon. To claim such a thing would be empirically wrong, because we can observe that, in reality, the Other is an Other Subject, who acts upon us as Object in the very same way which we act upon them. If we deny the free and equal status of the Other—if we act to remove their humanity from them—then they will do likewise to us. And then, so-too will we also be no longer free-and-equal; no longer human in their eyes.

Then, we’ll all just be monsters together… because we’ll have made each other so.