"What is 'Human'?" : Being and Becoming Human; On the Definition of Humanity | Existential Basics 5

a Short Essay for the Modern Existentialist

Hidden so deep in veils of deceit, Imprisoned in twisting spells— Are we the plaything of fiends, or simply the dreams That we're telling ourselves...?—Keiichi Okabe (岡部啓一) | Nier Automata: Ashes of Dreams

1 | Subject and Object; One-in-the-same

In our previous article:

We explored the philosophy which forms the foundation of what we call Nihilist-Absurdist theory. We established there that Nihilists and Absurdists both believe that:

Metaphysically Objective truths are the only “real” truths, and that our fundamental inability to access them means that we are only left with fake truths. That none of the things which we think of as “real”… can actually be considered truly “real”.

Because of their investment in their dogmatic system, Nihilists have managed to reason themselves into believing themselves to be pure Object. They think that, because the consciousness that they believe they feel is just a trick played on them by their biology—that they can only ever be acted upon by their circumstances—they’re therefore completely and irreconcilably impotent, with no Agency or Power to act.

Absurdists, on the other hand, believe that these fake, Subjective “truths” that are left behind are the only thing that we have—the only thing we’ll ever be able to experience at all. And so, they manage to reason themselves into believing themselves to be pure Subject. They believe that, because our world is fake, we’re therefore perfectly free—with all the Agency and the Power to do whatever we want in the world.

Here, though, we observe once again how the Nihilist and Absurdist are both empirically wrong. It can’t, after all, possibly be the case that we’re purely Objects in the world, because we believe that we think and feel within our minds. If we were, in reality, just Objects—like a stick, or a rock—then we’d be, in the first place, incapable (at least, to the best of our knowledge), of believing that we’re anything at all.

To believe—to be capable of thinking at all—implies that we must first exist in at least some capacity. After all, if it were the case that we didn’t exist, then…

What could be the thing that’s doing the thinking?

It also, however, can’t possibly be the case that we’re purely Subjects in the world. We know empirically that we must also be Objects—after all, we’re always constantly being acted upon. If we were pure Subjects, then that couldn’t be the case—but, in reality, we can observe that we’re biological beings which exist within the constraints of a physical world. Even beyond that, however, we can observe that we are social beings which live within the constraints of a social world.

We can’t be purely Subject in the world—can’t be purely actors, because we’re acted upon. We also, however, can’t be purely Object in the world, because we’re also actors within it, who act upon it. We can’t be only either Subject or Object, because we can see that, empirically, we’re both—one-in-the-same, all at the same time. In every moment, as people and as Agents, we’re both Subject and Object.

We both act… and are also acted upon.

2 | The Hermit

As human beings, we don’t each live in our own vacuum. We can’t be individual Subjects by ourselves… because that wouldn’t make any sense. After all, “individual” is a contrastive descriptor—a word which describes a specific person in contrast with a general “everybody else”. That means that the concept of “the individual”—the Subject—can only exist in contrast against its opposite; “the collective”—the Objective—or, essentially:

All the other people that aren’t this one.

After all, if there was no one else—no other person to stand in contrast against the individual-self—then what could it even mean to be an individual?

An individual… what?

…

As human beings, we’re only truly human when we are… a We. When we’re together.

You and I are social animals. The need and desire for contact and companionship is hardwired into our biology. We only function in a way that we’d consider “normal” or “human” when we’ve had the chance to live and learn in the company of Others. In other words:

We only act like “people” because we learned how to be people… from other people.

Sartre said this:

In the existence and the world which we share with one another… and what’s popularly considered to be “reality”.

…

Let’s say that there’s a man who decides one day that he’s fed up—tired of living his everyday grind. He packs his bags with essentials and leaves, walking down toward the docks. He hires a local fisherman to take him out to one of the uninhabited islands off the coast. There—he thinks—he’ll become a hermit, and live the peaceful, solitary life of which he’s always dreamed.

When he finally arrives on that island’s shore, he says this:

Ah… I am alone at last.

Now, we can say pretty conclusively that the hermit is free to make this choice. That he might be considered generally eccentric, but that he’s free to exercise his Agency in his pursuit of abandoning society. What we can never say, though, is this: that in choosing to abandon society, he now exists all alone in the world—as purely and only either Subject or Object, because he necessarily must still be both; just still one in the same.

He can’t be purely Object, because—even though he’s now alone—he still has choices that he must make. He also can’t be purely Subject, because he can still be acted upon—for example, by the wild animals living on the island, and also by the physical world itself; by the sun and the rain, and the seasonal hurricanes which batter the island in the summer months of every year.

And, while it might be true that he’s given up his continued involvement in society, it will never be the case that he can consider himself to no longer be an Object, because he’ll always still have been acted upon as a product of his society. After all, he was born to a mother—grew up alongside Others. Even if he never had any friends, he still spent years watching and learning as human children do—by observing the behavior of Others. For all his life, he had access to social contact—to the opportunity to interact with the Other. That is what has made him human—and that is what makes us human. And now, no matter what choices he might make, nothing can undo what’s already been done. In other words:

Nothing that we can possibly do in the future… could ever make us any less human than what we’ve already become.

3 | The Wild-Child

Here’s another question:

What could it even mean… for someone to “become” human?

Doesn’t that seem like kind of a stupid thing to say? After all, in the first place… aren’t we all just born human?

Well, it’s obviously not up for debate that we’re all biologically human—and that makes us all human in a sense. However, there’s another sense in which none of us are born human—and that’s the sense in which our human biology, alone, does not necessarily confer upon us all the basic characteristics that we might consider to be typical or inherent to every single human being. In other words:

We’re not born walking and talking like any normal, average person. Those are things that we learn—and we learn them through observation of one another.

What makes us… “us”—what shapes us, and distinguishes us as human—is the choices that we make and the actions which we take; our goals and desires, and our unique, individual experience. But, just as much as it’s any of those things, it’s also equally our inter-actions with Others; the things that we choose to do together, and our unique, collective experience. In other words:

The way in which the gaze of the Other fixes us in a common reality.

…

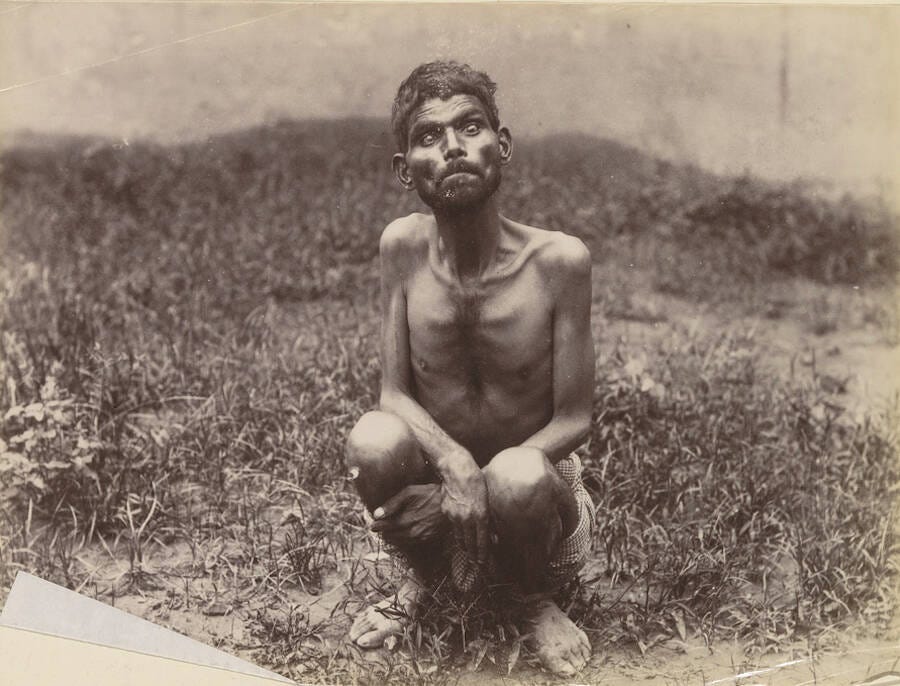

In the 1700s, a feral child around the age of 12 was found roaming the forests of southern France. Today, he’s known as Victor: the Wild Child of Aveyron. When he was discovered, he was naked—his body covered in scars and callouses—and he was unable to speak or form words. Rather than just being mute, it was discovered that, in reality, he’d just… never learned how to talk. The evidence here seemed to point to the theory that Victor had lived alone in the wild for probably most of his life. That, at least, was how it seemed to one Jean Marc Gaspard Itard—a doctor of the time. He remarked, after all, that when Victor was discovered, he resembled less of a man… than a beast.

Itard adopted Victor, making it his mission to try and “civilize” the boy—in other words, to try and teach the boy how to be human; to walk and talk like a man. He put him in clothes and cut his hair—then he began to instruct him, trying to imprint onto the boy the two traits that Itard believed made people human—two fundamental characteristics that separated beast from man. For the Doctor, these were language and empathy; the two traits that, together, allow the human individual to live and exist in the company of Others. Two traits which, today, many would consider to be fundamentally normal—essentially inherent to the nature of human beings. After all, when we look at examples of people who are missing these traits—who can’t walk or talk or intuit feelings the same way as other people do—we consider them to be abnormal. To be disabled in some way—broken, and in need of “fixing”… because they’re missing something.

In the end, the Doctor was unable to “civilize” Victor. He noted that, while Victor did make some progress in acquiring empathy, he was never really able to learn or understand language… at least, to any meaningful degree. The Doctor came to think of his work as a failure—and so, giving up, left Victor in the care of an older local woman. There, he lived the rest of his life, eventually dying of Pneumonia at the age of 40.

Feral children are incomplete. There’s something missing from them—something that we’d consider fundamentally human—but that can never be recovered… because it was never there in the first place. It wasn’t missing at birth—was never a function of their base biology. They weren’t born without their humanity—instead, it was denied to them. In their process of becoming human, they just simply weren’t provided the opportunity to become… complete.

As human beings—as social animals—our interaction with the Other is fundamentally what defines us. We think and we learn and we grow together, and we shape one another through our socialization. We speak and communicate through our use of language—we feel and know through our use of empathy. That is what makes us human.

We are born as Nothing—as children with nothing more than just human biology. Our biology—the simple fact that we are Beings—doesn’t make us human by birthright. What it does, instead, is give us the chance—the fundamental potential and opportunity—to become human.

We are human, you and I—not by right of birth… but instead because we’ve made each other so.

4 | Conclusion

Sartre says this, that:

Man is not and cannot be only just Being alone—not only a Subject within a world of Objects; or Dasein, as Heidegger might claim. This is because Man is necessarily, after all, also equally just as much an Object of the world. Beyond that, Sartre goes on to flip Heidegger’s terminology on its head in order to demonstrate that he’s actually empirically wrong. Sartre argues, after all, that Man’s nature as a Subject doesn’t make him a Being. Instead, Man’s Subject-status actually makes him a Nothingness.

We are born into the world tabula rasa—as blank slates, as Locke would say; as children with nothing but human biology. Because we’re Fundamentally Subjects—because we’re agents who are personally responsible for our own actions—we are therefore undefined… that is, until we make our choices. Man is defined by his choices—by how he chooses to exercise his Agency, and how he chooses to act within the reality which we share. That is how a Nothingness becomes a something—a Being.

Man isn’t either an Object or a Subject—not either a Being or a Nothingness. Instead he’s both, all at once—

Object and Subject—Being and Nothingness.