"What is Truth?" : On the Nature of Reality | Existential Basics 1

a Short Essay for the Modern Existentialist

Thus there is a feeling… that when you get right down to it, a lot of philosophy is just old white guys jerking off. Either philosophy is not about real issues in the first place, but [instead] about pseudo-problems; or when it is about real problems, the emphases are in the wrong places; or, crucial facts are omitted, making the whole discussion pointless; or the abstractness is really [just] a sham for what [you and I] know, but are not allowed to say out loud.

1 | The Meaning of Philosophy

What is philosophy?

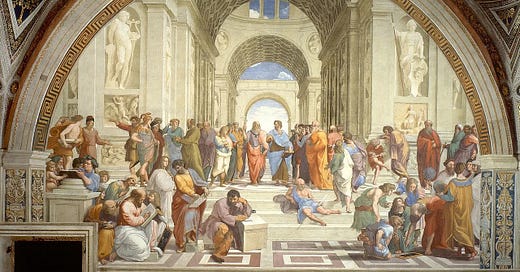

In the time I’ve spent both in and out of academia, I’ve met more than my fair share of people who seem absolutely convinced that they know exactly what philosophy is. It’s a bunch of old, dead white guys sitting around arguing back and forth about a bunch of arcane shit that can’t possibly really matter.

And honestly? They’re right—

About... half the time.

What we’re interested in, though, is that other half—the half that lives up to the name of the word.

Here’s the Greek:

Φιλο | filo: to love

Σοφία | sofia: wisdom

Where the word comes from, and what it’s supposed to mean.

That’s filo: “to love”, and sofia, which means “wisdom”. Put ‘em together, and what you get is “the love of wisdom”, or something like “the pursuit of knowledge”.

What that means for us, though, is that we can turn it into something tangible—something concrete. We can call it “the search for truth”, and we’d still be just about on point. But now, that leaves us with an even more basic question that we’ll need to answer first, which is this:

What is “truth”?

Well that’s… pretty simple, actually.

I look—I see. I can hear, touch, taste, and smell. I perceive the world around me. Sure, I can’t know for sure that anything I think I know is real… but it does seem like it makes perfect sense to just assume that my world is real if I can see that it’s real—that is, unless I find some other reason to believe that it’s not.

But that’s a different conversation. We’ll address that next time, in:

For right now, let’s break what we’ve already done down a little more.

First, I asked a Question: “What is “truth”? How can we know that what we think is true is actually the truth?”

Then, I formed a Hypothesis: “There’s a sense in which I can know truth because I can go out into the world and confirm whether or not the things which I see match up with the things I believe.”

Next, I took Data—I observed the world—and found evidence that it was actually the case that I can go out into the world and confirm whether or not the things which I believe match up to what I can see.

And finally, I confirmed my Theory: “In the absence of evidence to the contrary, the best I can do is assume that I can know truth and assume that the reality which I see is real.”

Now, what does all that look like to you? Was that philosophy? That was just science… right? It was logic, and simple math—putting two and two together. It was rational, and testable, and provable… but that’s what philosphy is—or, at least, what it must be by its etymological definition. Philosophy is, after all, the “love of wisdom”—the “pursuit of knowledge”… and science is, by definition, knowledge.

This is what we call empirical philosophy: a pursuit of knowledge that’s informed by empirical methodology.

In other words, a scientific philosophy.

So, back to the question at hand:

What is philosophy?

Well, what it must to be—what it was originally—was basically empirical, and basically scientific. You must, after all, first use your eyes to look and observe—to gather data. Then, you can use your brain to think that data through. After all, if you don’t first somehow observe the world… then how can you have any information to think through?

To figure out how reality actually works: that’s what philosophy’s supposed to mean.

2 | The Rejection of Inherence

Philosophy is “the search for truth”—to take what you can see and what you think you know, and to use your brain to put it all together.

Let’s talk about that second half, then; the half that many people—especially me—think is wishy-washy, arcane armchair bullshit that can’t possibly really matter.

It’s called metaphysics, and what it is is “abstract theories that are based on assumptions that are essentially detached from the observable world”. But wait—if we think back to our basics; to the empirical methodology we explored earlier, then:

How can anyone form a theory based on assumptions that are detached from the observable world?

How can you say that you believe something is the truth… if there’s no way that you could’ve ever possibly discovered information in the world that could confirm that belief as actually true?

The problem with this latter half—with this kind of highly-academic, un-empirical philosophy—is that it’s not empirical. It’s irrational and detached from the real world, and so it never gives us any tangible reason to think that its truths are reliable. This are what we call a dogmatic philosophy—a school of thought which picks and chooses what kinds of evidence it’ll take. These dogmatic philosophers don’t care about trying to reach the truth (which, in the first place, is the purpose of philosophy) because they believe that they already know what the truth is. And, after all:

Why would you go out and look for something… if you think you already have it?

This is what Nietzsche says—that dogmatists are the ones that he calls “dreamers”. The ones who closed their eyes a long time ago, and now live in their own fantasy world… completely detached from reality.

A dogmatic philosophy is any pursuit of knowledge which holds as its core beliefs that:

1: There are properties of existence which are absolutely inherent to it, and

2: That we can know these inherent properties as objective facts of reality.

And so, what makes a philosophy dogmatic is a belief that we can know that something is absolutely true, even though we can never observe or confirm whether or not that’s the case.

So, Nietzsche calls it “dogma”, or “objectivity”. Sartre calls it the “spirit of seriousness”, or sometimes “the belief in essence”. It doesn’t really matter what we call it—after all, they all mean the same thing: just any way of thinking which doesn’t come from an empirical base.

I like to call it “inherence”—after all, a “philosophy of inherence” is just exactly what that word means:

A belief that things are supposed to be some way, without any evidence as to why that’s the case—and, that it’s wrong to think that that might not really be the way things are supposed to be.

To doubt… is evil. To think is evil, because somebody else already did all the thinking for you. All you need to do is follow and believe—

That’s what dogma means.

3 | Conclusions

So, there’s your first lesson in existential philosophy. We, as existentialists—and therefore as empiricists—must reject the idea of inherence in all its many forms. We reject dogma, and any form of dogmatic philosophy—any pursuit of knowledge or truth that claims to know anything which we wouldn’t be able to discover for ourselves.

Innocent until proven guilty.

No crime unless there’s proof of a crime.

Absent until proven present.

Nothing can be considered truth until it’s proven that it is.

All men are born of a woman.