5 | BEING & NOTHINGNESS : On Subject & Object (in an Existential Sense)

Method & Madness | Book I : Existential Fundamentals

Man is condemned to be free—condemned because he chooses not his own creation, yet still is made with freedom foisted upon him. Condemned, for once he is thrown into this world, he becomes responsible for every feat or failure done by his will. He alone is responsible for his choices; he alone may commit meaning to his existence.

—J.P. Sartre (ab. M. Hise)

The year is 1943. France had fallen—red-and-black banners now flying proudly over the streets and halls of Paris. In the midst of the angst and turmoil of World War II, Jean-Paul Sartre released his magnum opus—L'Être et le néant (Being and Nothingness)—a book about freedom to a city held in chains. Three years prior—while captured and jailed as a prisoner-of-war after the fall of the Maginot on the eastern front—Sartre had read the seminal work of one Martin Heidegger, a prominent phenomenologist; a Nazi philosopher1.

In 1927—six years before the party rose to dominance, and thus six years before he joined up—Heidegger published Sein und Zeit (Being and Time), his exploration of the fundamental nature of Being2. In Being and Time, Heidegger describes the nature of a person as fundamentally characterized by the fact that he is thrown3 into existence. Heidegger asserts that the best way for a Being (thus-thrown) to be is to live his most authentic4 life; to acknowledge the fact that we all die in the end5, and thereafter to choose to break free from and transcend the faceless6 existence of normative conformity. To become what he calls Dasein7—that is, the “true-self”.

Dasein, to Heidegger, represents the pinnacle of what Man can be—an authentic individual; a fully-actualized potential. He asserts, in effect, that Man is Being, destined to rage against and transcend the dark abyss of death and obscurity—of Nothingness—in which all things inevitably end. To actualize as Dasein is to do great things and be thus remembered, at once transcending both inexorable death and faceless obscurity; to be held in memory as having achieved one’s own historistic8 destiny.

Thus, it’s the case that Heidegger—like Camus—believes in the Absolute-Subject; the nature of Man as pure Being.

Here, however, Sartre contravenes; turning the Heidegger on its head. He asserts that, in reality, Man does not represent Being—but instead, is a manifest Nothingness.

We cannot demonstrate, after all, that Man is thrown into the world with a destiny to fulfill; a duty to actualize into his historistic potential. Instead, it’s the case that we do observe that Man is cast into his existence tabula rasa9—featureless and still yet-to-be-made, possessing nothing but the simple Facticity10 of his basal biology.

It isn’t the case, in Sartre’s words, that Essence precedes Existence; that we are born defined by an essential authenticity—an Absolutely-Objective goal—which we should strive to achieve. Instead, it’s the case that Existence precedes Essence11—that we are born with nothing… and, thereafter, become defined in the world through our actions; our Individual-Subjectivity.

It should be obvious12, after all, that—like Phantasmus—we can obtain no evidence for an Absolute-Objectivity; a historistic destiny. We can observe, however, that in reality history is made—a story which follows after the exploits of our Agency.

We cannot know that we should do anything—instead, only that we can do things.

Man is condemned to be free—and thus, he exists as a Subject in the world, responsible for his own definition. We are condemned to be free—thus, there is but one situation in which we can hold no power to decide: that is, the fact that we must always decide. We are always in possession of our Agency—our ability to act within our situation. Even when circumstances change—when we’re coerced, imprisoned, or otherwise pressured by externally-imposed constraints—we still possess the capacity to decide. Even when you feel that you have no choice—even if you choose to not decide—that remains still the choice you’ve made.

A choice to believe that you have no choice.

A choice to not choose.

To Heidegger, our destiny is made for us—and we, made to reach out and grasp it; our Existence determined by our Essential nature and the context into which we’re thrown. To Sartre, our fates are our own to make—our Essence defined by our actions in the world, and the way which we choose to Exist.

Man is not Being, but is first a Nothingness. We have no grand destiny to fulfill, but are cast instead into a world which already exists—itself, the Being—while we ourselves remain Ambiguous; still yet-to-be-made.

We exist not in a state of constant being… but instead of dynamic becoming.

The year is 1800. A young child—about the age of 12—emerges from the forests of Aveyron; a hilly region in south-central France. He is naked—his body covered in nothing but dirt and scars and callouses. He walks and runs on all fours, and is unable to speak or form words. It’s discovered that, rather than being mute (or otherwise physically unable), he had in reality… simply never learned to talk. Today, he is known as Victor; the Wild Child of Aveyron.

It's likely that Victor had lived alone in the wild for the majority of his life, drawing close to human civilization only for the same reason that animals do—that is, in search of easy food. That, at least, was how it seemed to one Jean Marc Gaspard Itard; a medical student of the time. He remarked that, when Victor was discovered, he appeared to be less man… than beast.

Itard adopted Victor into his home, making it his mission to “civilize” this boy. Itard would attempt, in other words, to teach the boy how to be human; to walk and talk like a man. He put him in clothes and cut his hair, then began to instruct him—intending to imprint onto the boy the two traits which Itard believed made humans… human; two fundamental characteristics which separated beast from man. For the aspiring doctor, these were language and empathy; the two traits which, when held together, allow human individuals to live and exist in the company of Others. Two traits which, today, most would consider to be fundamentally normal—basically inherent in what it means to be a human being. When we look at examples, after all, people who’re missing these traits—who can’t walk or talk or intuit feelings the same way as other people do—are considered to be abnormal; disabled. We regard them as broken, and thus in need of “fixing”… because they’re missing something.

In the end, in spite of his efforts, Itard failed to “civilize” Victor. He noted that, while the boy did make some progress in acquiring empathy, he was never really able to learn to utilize language to a meaningful degree. Thus, Itard admitted defeat, moving on to better and brighter things. He left Victor in the care of an older local woman, where the boy lived out the rest of his life—eventually dying of Pneumonia at the age of 40.

We all begin as human in a sense—that is, that we’re cast into this world in possession of fundamentally human biology. There’s another sense, however, in which none of us are born human—in which we’re born as Nothing—because our basal human Facticity doesn’t confer upon us the full range of “inherent” human characteristics.

We aren’t born walking-and-talking like any normal, average person. “Normal” is something which we acquire—which we become. “Normal” is something which we learn and adopt through interaction and observation; via socialization.

Sartre said this:

The gaze of the Other fixes us in Facticity;

In the existence and the world which we share with one another—what’s popularly considered to be “reality”.

The human being is a social animal. Our need for mutual contact is hardwired into our biology. We’re only truly human when we’re connected; when we exist within a tribe—a society. We think and learn and grow together, shaping each other through mutual experience. We speak and communicate via common language—we feel and know by means of empathy.

What makes us—what distinguishes us as Individuals—is the choices we make and the actions we take; our goals and desires, and our unique, Subjective experience. But what makes us human—what defines us in the world—is the way in which we’re perceived by Others: our interactions and adventures, and the mutual projects we choose together; a collective, Social experience.

Feral children are incomplete—missing something we’d assume was fundamentally human, yet which somehow also can’t be recovered or restored to them. It wasn’t absent at birth—they weren’t born without their humanity. Instead, it was denied to them in their process of becoming.

We are born as Nothing—cast into Being as flesh and bone. Our biology—simply that we exist—doesn’t make us human by birthright. What it does, instead, is lend us the potential—the opportunity—to become human.

The gaze of the other fixes us in Facticity—and:

We are not human by birthright—but instead, because we make each other so.

Husserl13 leaves us with the idea of Intersubjectivity:

The relationship formed between individual Subjects via their interaction.

In other words:

The connection between people.

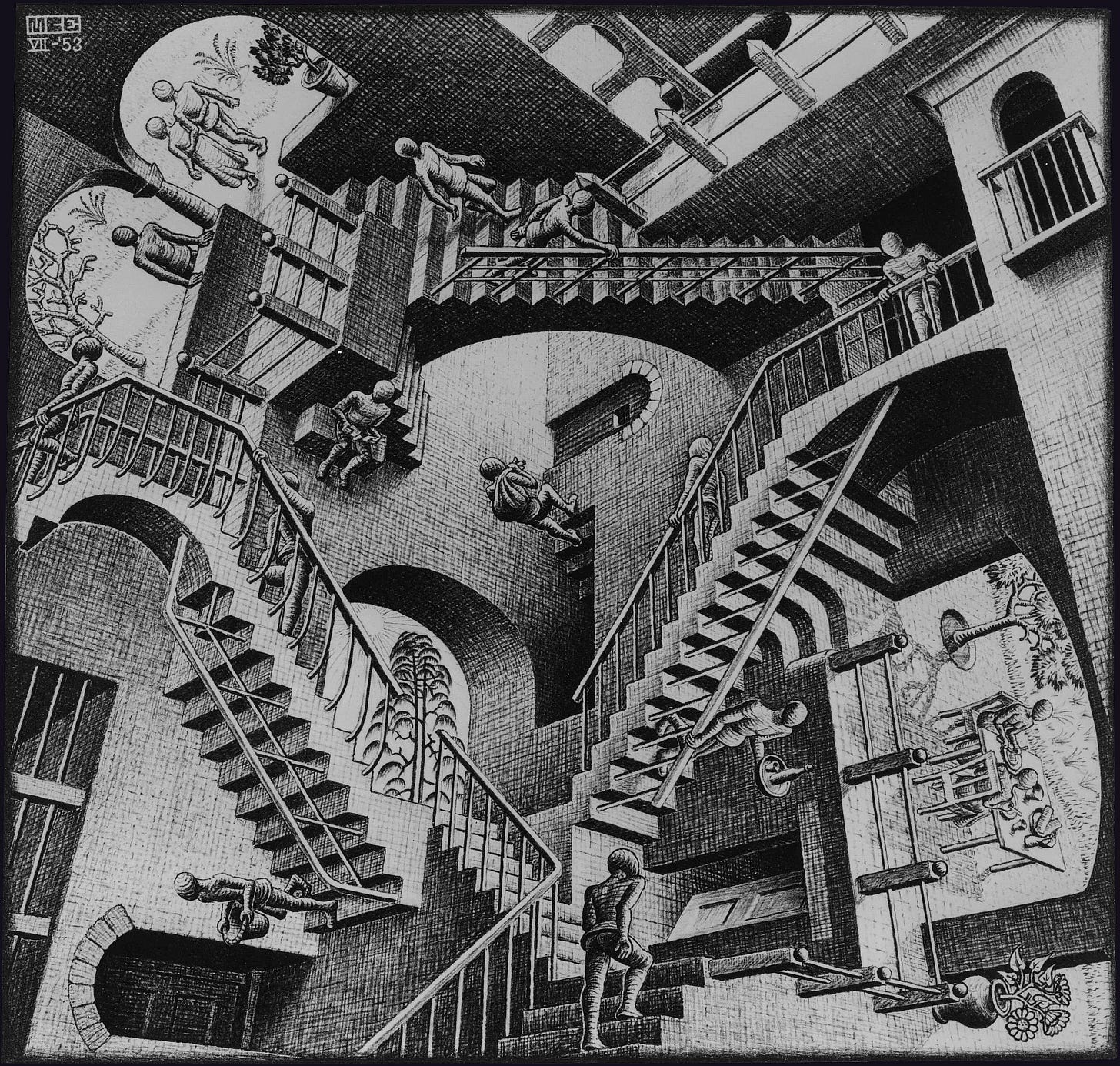

We can see (i.e. empirically observe) that we are not purely Object-of-the-world—as the Nihilist would believe—because of the simple fact that we possess Agency. Equally, however, we cannot be purely Subject-in-the-world—as the Absurdist or a Heideggerian might claim—because we cannot observe that the world wages a theoretical oppression; an absurdity; against us… nor can we know that we’re cast into our existence in order to actualize into a metaphysical destiny. Instead, in our physical, observable reality:

We both act… and are acted upon.

Subject: an entity with the Agency to act in the world; to perceive and affect it according to its will.

Object: a thing in the world which can be acted upon; observed and manipulated, thus lacking Agency.

The human being stands as a fundamental contradiction14. We exist in the world not as Subject or Object, but instead as both, all at once. We are evidently Subjects, holding a freedom to act in our world; and yet, at once, are also Objects; our freedom constrained by the bounds of that world’s physical15 potential. Yet, it’s clear to see that this isn’t our only circumstance; not the only way in which we’re situated—our freedoms bounded—our selves Objectified in our existence.

The human being is a social animal; the gaze of the Other defines us in the world. We are Agents to ourselves, in our own minds; but to Other-Subjects16—who look out onto the world and see themselves as Agents—you are a thing in the world to be acted upon.

You are Subject in your mind—but you are made Object in their minds.

I think that we often commit ourselves too much to the idea of our selves as individuals. We place too much emphasis on our own experience—too much weight on our own perceptions and beliefs.

But you and I… have never been alone.

We are alone in our experience—in our Individual-Subjectivity. But it’s also equally true that, for the our entire lives, we’ve lived in the company of the Other. We reach out for one another, shaping and molding each other into people. We’re desperate to connect—to form relationships and exchange information; to construct new experience together. We form a network—we uplink, in effect—becoming part of a social cloud-consciousness: a collective Subjectivity. We choose to trust—to believe that the stories of the Other hold truth; that they are thus, in turn, capable of informing and confirming the validity of our own experience.

We come together to form societies—we make culture and establish law. We forge together an accretive consciousness—a social memory. Our individual knowledge and power join together to form a collective Agency—an aggregate fantasy. This is the nature of our “reality”—our Intersubjectivity, our Facticity, and…

Our Social-Objectivity: the way in which our collective Subjectivity appears to us all.

When we say the words:

“Objectively true”

What we mean to say is that something is “obviously the case.” But when we say that something is “obviously the case”… do we really mean to claim that it’s an Absolutely-Objective truth?

Well… obviously not. After all, when we speak of “Objective truth”, we don’t intend to call on that “truth” as absolute fact.17 Instead, we mean to identify a truth of social consensus.

An “Objective truth” is not an Absolute-Objectivity. Instead, it’s a Social-Objectivity.

Thus, we observe that, in reality, the human being lives at once within three distinct modes of existence. These are:

Individual-Subjectivity: where Man is a Subject in a world of physical18 Objects, with the ability to experience it and to act to affect it according to his will.

Absolute-Objectivity: the metaphysical19 world of Objects which we must infer that we exist within—which cannot be directly observed, and thus cannot be proven to exist.20

Social-Objectivity: where Man is a physical Object in a world of Other-Subjects; where he is observed, judged, and thus affected and defined by the will and opinion of Others.

This is the nature of our aggregate Subjectivity: that it allows us to formulate a type of Objectivity—one composed not of theoretical absolutes, but instead of collective truths. This is Social-Objectivity—a Subjective Objectivity—created by means of aggregate fiction, and the collective exercise of individual Agency.

This, to Sartre, is Facticity:

The physical fact of our world; the reality we make together.

This social reality—for all intents and purposes—is, itself, reality. After all:

Truth is consensus which we create together—and…

Meaning is the value which we assign with the Other.

We are not and have never been either Object or Subject—Being or Nothingness.

We are Objects. We are Subjects.

We are Being and Nothingness.21

This claim is often disputed in attempts to defend Heidegger’s character against his politics, and to separate his philosophy from its implications. This is in spite of the fact that Heidegger was actually a vocal and active member of the NSDAP, himself declaring that his philosophy was the motiving force behind—and therefore inseparable from—his politics. He grew disillusioned with the party, in fact, only once he’d vied for and failed to attain the post of “party philosopher”—by which, if he’d succeeded, he would’ve become one of the most prominent Nazi intellectuals—and thereafter retired a sore loser to minor role as a professor of philosophy, where he preached that his politics remained unchanged, but that it was the party which had lost its way.

Sein. “Being”. Essentially, “existence”.

Geworfenheit. ”Thrown-ness”. Essentially, that man is cast into and situated within a physical and social context: a specific point in history.

Eigentlichkeit. “Authenticity”. Essentially, to be true to oneself by living up to one’s own potential; one’s destiny.

Sein-zum-Tode. “Being-towards-death”. Essentially, the fact that our lives are oriented around and defined by their finitude; that we all die in the end.

das Man. “They-self”. Essentially, an ambiguous plebian; to be “one of the crowd”.

Dasein. “Being-there”. Essentially, “an existence”, or “the manifest being”. In Existentialist terms, an “Agentive individual”, or simply a Subject.

For Heidegger, existence is fundamentally “historical” in the sense that all action occurs within a context or place within Time (as in the title, Being and Time, which would suggest that Being exists within space-Time as a Subject in a world of Objectivity). Historicity is a ubiquitous awareness of the historical continuity to which the Being belongs—a transcendental awareness of one’s greater context (i.e. Facticity) in all endeavors which one chooses to take on.

As in Locke. A “blank slate”.

As in Sartre. The apparent state of existence or reality—one’s circumstances or situation.

In the course of their philosophical dispute, Heidegger famously retorted that “the reversal of a metaphysical statement is still a metaphysical statement”, thus accusing Sartre of twisting his philosophy, and disparaging him as having grievously misunderstood his comprehensive phenomenology. To any remaining Heideggerian in the audience, I would ask this question: Did you read chapter 2?

Once again, assuming that you are neither deluded nor insane.

A prominent philosopher and Heidegger’s teacher in phenomenology. Also, notably, a German Jew in the year of 1933—the year when the NSDAP’s Adolf Hitler wins the chancellorship of Germany.

As in Sartre.

Physics is a science; a form of empirical high theory. Therefore, theoretical physics is metaphysics (as defined in chapter 2).Thus, to say “the theoretical bounds of a world’s physical potential” is functionally the same as to say

“a world’s metaphysical limits.”

In the Problem of Other Minds, we ask the question: “How can we be certain that there are, in reality, Other minds?” While we obviously can’t be absolutely certain… we can be certain to a reasonable degree. Wittgenstein says: “Behavior is expressive of mind.” What this means is that it’s reasonable to—if there’s a thing that behaves as though it has a mind—just assume that does have a mind, and that it is an Other mind, until we’re somehow proven wrong. If, after all, “humanity” is nothing more than an assigned status, then it’d be reasonable to confer human status upon anything which performs “humanity” well, because a thing which acts human… is a thing which commits human acts, which we judge as humane within the world.

That is, of course—once again—unless you are objectively deluded or insane.

That is, empirically-physical. The perceived reality within our senses.

That is, theoretically-physical. The speculative reality beyond our senses.

This is neither a phenomenalist nor a physicalist statement, as these two schools of thought represent yet another reductionist dichotomy. It should be obvious, after all, that the fact that one’s experience of an object is composed of empirically-physical phenomena does not preclude the fact that we must still posit that an inaccessible, theoretically-physical (and therefore unknowable) object serves as the source of the phenomena. The alternative, after all, is to assume that the phenomena which we experience are called forth from a blank void, which—to me, at least—seems like less-plausible theory.

To Heidegger, one’s historical facticity is necessarily integral to one’s Being—thus, it’s not the case that he was a Nazi in spite of his philosophy, but instead that he was a Nazi specifically because of his philosophy. His facticity, after all—his historicity—demanded that he embrace his situation, and thus strive to achieve his maximal potential within his place in Time. To Sartre, however, one’s social facticity is simply the way in which he’s perceived and defined in the world by the Other. What this means is that—in effect—to deny the human status of the Other may not be some kind of absolute moral-ethical evil… but what it is—in reality—is simply factually and empirically incorrect. We observe, after all, that the Other is an Other-Subject, who is theoretically as equally capable of acting upon us as we are of acting upon them. Thus, if we act to deny their humanity, then they will do the same to us, and none of us will be human any longer in each others’ eyes. Then, we’ll all just be monsters together… because we’ll have made each other so.