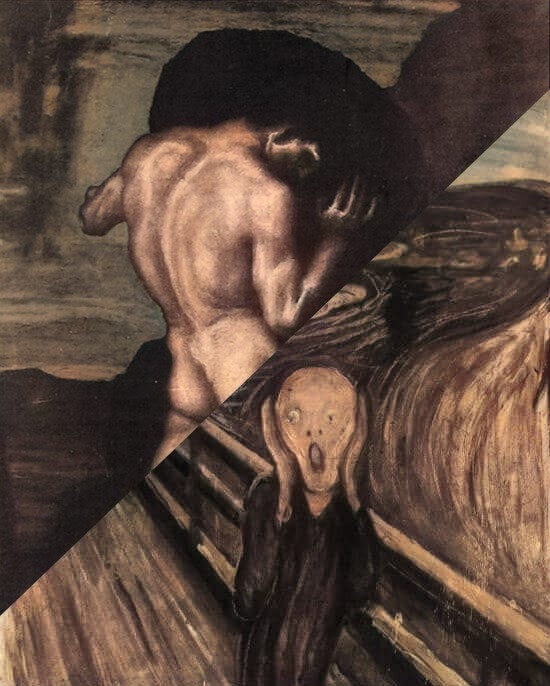

4 | NIHILI⬥CARMEN : God is Dead & Everything’s Shitty

Method & Madness | Book I : Existential Fundamentals

Cynicism is the only way by which baser souls will stray near honesty. Anyone who were truly above them would thus take note of every snide quip or subtle sarcasm, and should feel only entertained when such a shameless clown or intellectual playactor so freely tips his hand.

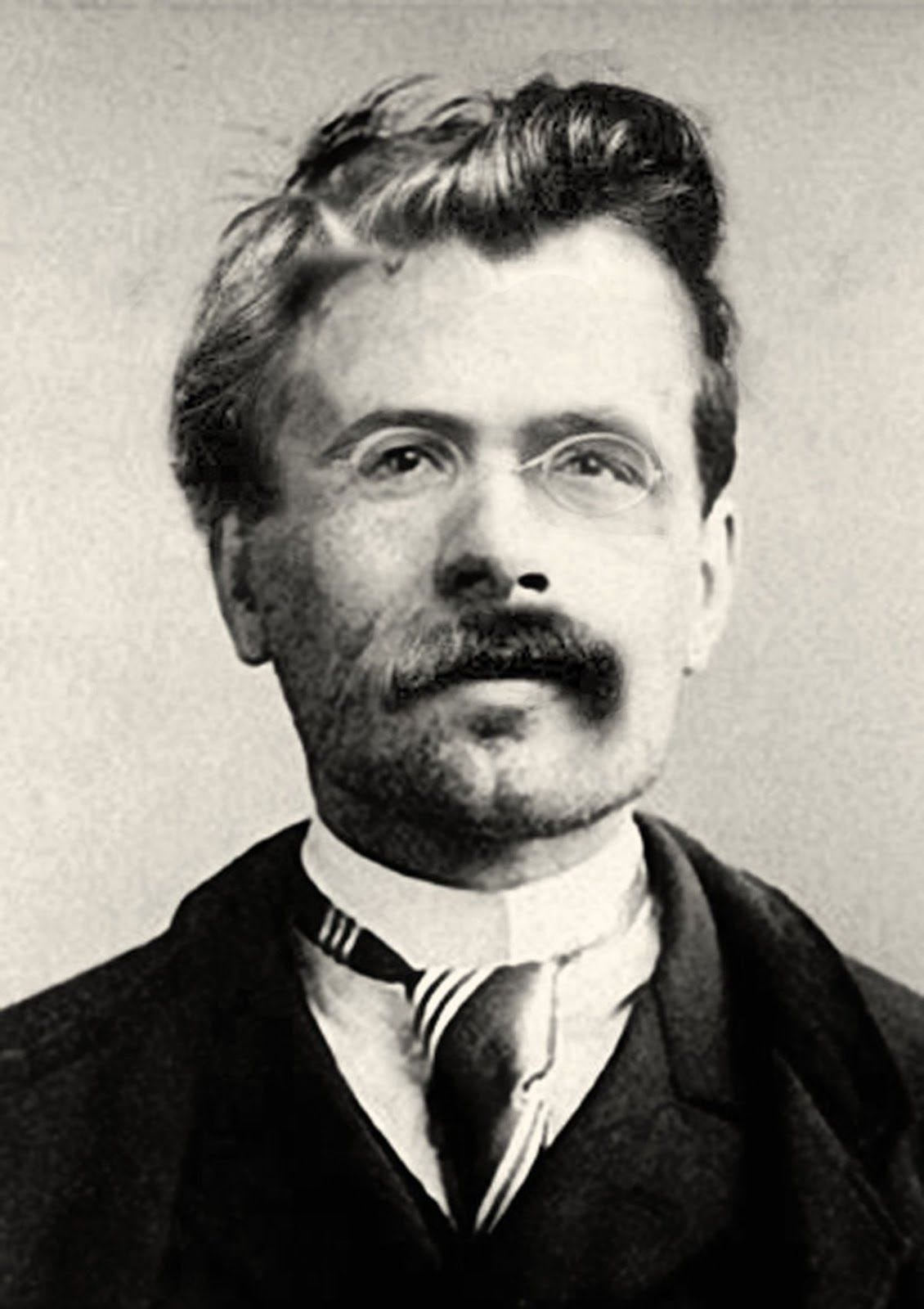

—F. Nietzsche (ab. M. Hise)

Alone. Alone.

You and I are each ever-alone. That is what sets us apart—

That is what binds us together.

We are the only ones who will ever see what we see—who will hear what we hear. Who will ever feel what we feel and know what we know.

I am the only me. You are the only you.

In this, we are together—together, in our isolation. Removed from one another without recourse, as islands set adrift upon a shimmering sea. Held apart for all eternity by a vast expanse of water; by experience, appearance, perception… and the difference which spans ever-between us.

We seek purpose, you and I—a place and a meaning which motivates our lives. We seek to earn the right to exist—

We seek to belong.

But if the things we hold dear—the things which define us: all our projects, values, aspirations, and absolutes—cannot constitute Objective truths, but are in reality just opinions and appearance…

If reality is fiction, existence not given, and Method simply reducible to Madness, then…

Why do we struggle? Why do we persist?

If we all just die in the end…

Then for what reason—what purpose—have we ever existed?

In our world—as conscious, living, experiential beings—we exist as:

Subjects: Agents who posses the power—the Agency—to act upon the world we perceive; to change it according to our will.

We experience the world and name its things, categorizing and thus transforming them into discrete units. These, we call:

Objects: the things in the world we observe and manipulate, devoid of the Agency to act.

Thus, a Subjectivity is a perceived truth—an Objectivity, a simple fact. We are as children playing in the sand, exercising our Agency; expressing our Subjectivity. Building, exploring, and destroying the Objects we create and perceive at our leisure.

To the Nihilist1:

Everything is meaningless.

The world is cold and uncaring—a bleak, barren wasteland devoid of any real, true meaning. We come and we go as ash and soil—and between, we are nothing but sacks of flesh and bile.

This is his truth—this is his fiction.

This is the mantra by which he lives.

Often, however, the Nihilist will style himself not necessarily as dark or depressive, but instead as a kind of… tragic realist. He thinks himself someone who’s simply come to terms with a fundamental, immutable fact of the world—a profound wisdom which is at once somehow both transcendent and obvious. The brute fact that—Objectively speaking—nothing is really, truly real, and that the universe itself marches inexorably toward a futile, meaningless end.

He believes that, because our Subjectivity is an abstraction—because we can’t access an Absolute-Objectivity—our existence is therefore fake; a lie, and a sham. Because our truth is derived from fiction, our Agency is therefore an illusion. Because our freedom is not absolute, it’s therefore nonexistent. Because meaning isn’t inherent to existence… it’s therefore inherently absent—and:

Because existence is inherently meaningless… we’re condemned to suffer and die for no reason.

And so, the Nihilist is left with just a handful of rational choices. He may decide to either:

Rage against the dying of the light, seeking retribution against the scam and the lie.

Scream and wail into the void and commit dramatic suicide.

Extol the futility of all actions and things (that is, including both rage and suicide), and thus persist in stoic silence, preparing to eventually die.

To Camus, suicide (both the fast and the slow kind) represents the most fundamental of philosophical questions; the first which should be asked by any self-aware mind. What, after all, could be a more pressing question… than whether or not one should live or die?

Life is possibility—opportunity. For so long as you live there’s infinite potential; a hope to obtain and experience joy, peace, love, and fulfillment. We fear death because it represents this end: the final evaporation of these things.

Life is possibility—but also, probability. As long as you live, there exists equal potential that you could be plunged at any time or place into a terrible world of rage, fear, struggle, or pain. Yet still, what remains a constant… is the promise of death: the final evaporation of all things.

And so, it’s the case that a suicidal state-of-mind doesn’t necessarily imply mental illness—instead, only that one’s situation dictates that the appeal of living is less than that of dying. When all hope is lost—when the allure of life begins to fade—the prospect of death grows ever-more appealing. Even when life has lost the lustrous glow of what-could-be… the meaning of death remains ever-the-same. It stands still, holding out its hand, offering one final possibility:

A freedom from life—an eternal release.

But here, at this point, is where Camus interjects—saying this:

It’s true that existence is utterly and inherently devoid of meaning—that we feel we must seek, but will never find, meaning in our lives. But…

Why does your existence need to be… motivated?

Why do I need a reason to be alive?

Regardless of whether or not you have meaning… aren’t you already alive?

Once you’ve reached this point—the point at which you’re willing to cast away your life… is there really anything left in the world that you can’t do? If before, you were willing to commit yourself to death—to surrender everything that you are and could be in exchange for simply nothing, then…

What do you have left to lose?

If everything is meaningless—our existence just a simulation—then what power on earth could be left to constrain you? What remains that could stop you from rising up in the midst of this pale, bleak world—from rebelling against your futile finality, and seizing everything that you’ve ever wanted for yourself? If the world is fake—a fiction, and a fantasy—then no consequences remain. When we die it’s all over anyway, so… why not stay a while instead?

It's a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity, after all—a chance to live your fullest life.

If nothing really matters in the end… then why take it all so seriously? Why let something that’s clearly nothing bother you… and stop you from doing everything?

What Camus offers us is called Absurdism2—a taste of his ultimate freedom. The understanding that existence is, in itself, a contradiction; an absurdity. He offers us what he calls “freedom from hope”—from feeling the need to strive toward some distant, unreachable goal or ideal; from conforming, and seeking to become what we’ve always been told that we should be.

It’s a freedom from the world—a freedom from responsibility.

Because existence is inherently meaningless… we are therefore absolutely free.

The Nihilist believes that he’s conclusively nothing—an Absolute-Object of the world—explicitly not an Agent because Subjectivity is only simulated, and therefore constitutes a fake, false reality.

The Absurdist believes that he‘s conclusively something—an absolute-Subject and Agent as a result of the cogito3; that is, explicitly not an Object because Objects don’t have Agency.

The Nihilist, in effect, ascribes to Determinism4, where the Absurdist instead believes in Free Will5. In this sense, the Nihilist and Absurdist are opposites—but in another, they are identical.6 At the outset, after all, the Nihilist and Absurdist both ascribe to the idea that:

Existence is inherently meaningless.

The only functional difference between these two philosophical positions is that the Absurdist is glad to live in this world; a world free from the consequences and responsibilities which inherent meaning (i.e. prescribed purpose or absolute ethics) would demand… whereas the Nihilist suffers his existence instead; oppressed by his circumstances.

The Nihilist and Absurdist both fundamentally agree; it’s just that the Absurdist is happy, while the Nihilist is sad. And this—at least, in my opinion—isn’t really enough to justify a distinct philosophical division.

And so, the fundamental problem with Nihilist-Absurdist theory is that they believe that:

Existence is inherently meaningless.

Their system of philosophy is founded upon an Absolutely-Objective assumption of inherence—that is, that existence is inherently devoid of meaning. They believe that:

Because the world isn’t inherently meaning-ful, it’s therefore inherently meaning-less.7

But this theory is broken, and doesn’t track. After all, if we retrace the path of the Nihilist’s logic, it becomes immediately clear that we can’t actually conclude from his reasoning that existence is inherently devoid of meaning—instead, only that:

Existence is devoid of inherent meaning.

We can observe empirically, after all—we can see, like Verus—that it’s likely that meaning isn’t inherent. But what we cannot observe—can never confirm—is that meaning is absolutely absent.

We can’t claim that we know existence to be inherently meaningless.8 Instead, it’s the case that we must infer that:

In existence, nothing can be inherent.

There may be no gods—no arcane, celestial powers which exist simply to guide our paths; no omnipotent spiritual beings which weave our strings of fate. But in our world—in our reality—things mean things to us. Meaning has never been Absolutely-Objective… but instead, is entirely Subjective.

Meaning is not inherent—but personal. Meaning is empirical.

Truth is knowledge that we create, and:

Meaning is value that we assign.

Existence is not inherently absurd—but instead, is fundamentally Ambiguous9. The fact that meaning—that purpose—is created doesn’t make that meaning fake. What it does is make that meaning ours; within our power to determine and define—within the exercise of our Agency. Existence is simply what we make of it—and we are each, in the end, the author of our own story.

God is dead… and we have killed him. How can we forgive ourselves—we, the most grievous of all murderers? The most potent and righteous dream of our world bleeds to death beneath our knives. Who is left to absolve us—to guide us? Is the gravity of this deed not entirely beyond us? Must we ourselves not now stand in his place—not don ourselves his crown of thorns—if not simply to appear worthy of this?

—F. Nietzsche (ab. M. Hise)

i.e. Schopenhauer, who embodies a kind of ascetic Quietism, or Cioran, who represents a deeply cynical Pessimism.

A philosophy which asserts that existence is fundamentally absurd—in essence: the contradictory state of being in which, despite the fact that existence is inherently and objectively absent of meaning, we as human beings continue to feel that we must seek it. Albert Camus (technically, the only Absurdist) advocates for an attitude of “rebellion”; that is, to understand and embrace the absolute freedom of living amidst the cold silence of an apathetic universe.

As in Descartes, wherein the cogito refers to “cogito ergo sum”, i.e. “I think, therefore I am.” This phrase implies that, because one observes that one is thinking, one must infer that one exists in the capacity of at least a “thinking thing” (e.g. if not an actual human being, then at least a brain in a vat) which exists, observing oneself thinking.

Determinism implies an absolute absence of freedom-of-action within existence.

“Free Will” implies an absolute presence of freedom-of-action within existence.

As in Sartre, wherein the concept of Agency exists beyond the simplistic dichotomy of Free Will vs. Determinism, and is the experientially-verifiable capacity of Subjects to act upon and shape their world. Wherein Free Will and Determinism respectively suggest absolute presence or absence, Agency instead refers to the empirically obvious degree of freedom-of-action which individuals observably possess within their circumstances (i.e. within their Facticity).

This is a common fallacy. A presented dichotomy does not guarantee a true dichotomy—that is, the fact that only two options are presented doesn’t imply that only two options exist. In this case, the fact that “meaning” is given the opposing suffixes -ful and -less does not imply that “meaning” is not being otherwise modified, such as if I were to tell you that there are two kinds of apples in the world—green and red—while neglecting to inform you that “colored-apple” can also be modified with other words, like “gala”, “crab”, “fuji”, or “honeycrisp” (or even that apples can actually also be a third color, which is golden or yellow).

Unless, of course, you are once again either deluded or insane.

As in Sartre & Beauvoir, wherein Existentialism asserts that existence is fundamentally Ambiguous—in essence, that the living being is a fundamentally malleable creature in a state of constant flux; subject to constant change. We begin as nothing—we come from nothing—and exist in a constant state of becoming; of creating and defining ourselves within the world through the act of existing.

Nice, but simplistic. I dare not say "naive".

Or, should I say, just some narrow rabbit hole. :)