3 | IDEALISM : the Righteous

Method & Madness | Book II : Archetypical Philosophies

The serious man is but a puppet in the hands of the values he serves. He is characterized by his rigidity—incapable of questioning or reinterpreting the values he has adopted. He does not inquire, nor does he seek to understand the world; he simply follows the rules and then demands that others do the same.

—S. de Beauvoir (ab. M. Hise)

When we were young, we saw the world in stark black and white. There was Child and Adult—sheep and shepherd; the Innocent, and the wise. But as we grew, we began to grasp a simple, daunting fact:

That the protected are expected one day to rise and become protectors themselves.

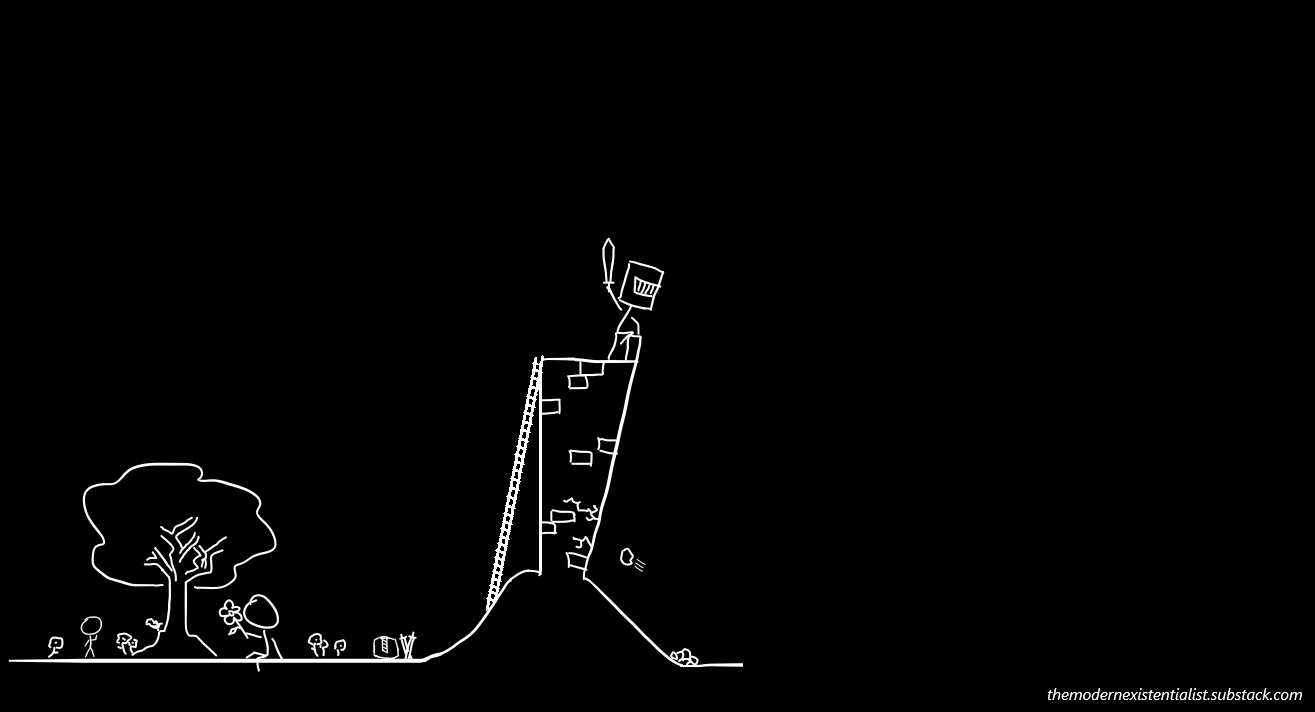

The Idealist is the man who chooses to stand and embrace this destiny—who believes that he is called to protect; that the freedom of the Innocent and Blameless are his charge, and that the light of civilization must be defended against the onslaught of a cruel, feral, unnatural world which pounds against his walls. He thinks himself a hero—Order, his shield; Truth, his sword—a defender who stands atop the wall, beating back the terrible monsters and demons which rage against its stones.

Taking up his Agency—embracing his fate—the Idealist is the man who believes that there are two kinds of people in this world:

The weak, and the strong.

There are those who are destined to rise as protectors, and those who are fated to remain protected. There are those who are strong—who have Agency—and, therefore, hold a unique responsibility to defend the world of Eden: the thin pale which shields the weak from the Evil horrors of the world beyond.

And so, as the man who’s embraced his Power, the Idealist believes that he’s finally achieved the coveted state of Adulthood. Where, as a Child, he’d turn his gaze upward to see figures strong and wise… now, he looks down and sees only the weak—women-and-children1—and thus believes that it’s finally his time to stand in the light. He believes he’s inherited the Adult knowledge of his forebearers—that inherent wisdom which allows him to speak of what’s Good, just, and right. Thus, he stands proudly atop the wall, waving his glimmering sword of Truth, believing in his heart that the light of Order—of civilization itself—deserves to outlast the darkness and Chaos of the world beyond.

The Idealist is the Righteous man—the defender who rushes atop the wall, ready to cut down any Evil which might try to scale its stones. When he does reach the top, however… he comes quickly to a sordid realization: that monsters have no need to climb. He begins slowly to understand that Evil and Chaos are immortal—and he himself only mortal—and that, for demons, an eternity remains for them to bash and tear away. Here, the sword he’s been given is useless—he may wave it, but can cut nothing. Thus, he eventually must realize that in order to embrace his destiny—to meet the fate for which he’s been called—he’s left with no choice but to leap down from atop the wall and fight Evil face-to-face.

In order to do what he’s told he should, he must first leave the safety of home. In order to defend his Eden, he must abandon everything he’s ever known. He must brave the dangers and the wicked temptations of the world beyond that wall, wading waist-high into Evil lands while still keeping faith and never succumbing—and, in the end…

For what?

So that the weak and the meek may live a while longer… and he, himself, may surely die?

And so, the Idealist—this Righteous man—is thus put to the test. Will he remain on the wall, waving his sword—deceiving himself into believing that he remains still a hero? Or will he leap from the ramparts into Evil below, trekking deep through muck and mire, and risk succumbing or even becoming… something else instead?

Philosophy: a mindset. a worldview. The way that one chooses to see the world, and thus approach living one’s life.

Αρχή | archí: origin

Τύπος | týpos: form

An Archetypical Philosophy is the logical basis of a person’s attitude, derived from observation of how he-or-she chooses to exist.

As in Beauvoir, where women are typically infantilized by a given society—that is, where “physically less-capable” is generalized into “generally incapable”—which then causes women as a caste (regardless of actual individual competence or ability) to be relegated to societal roles of lesser consequence. It’s often the case, Beauvoir claims, that Woman is treated like a “perpetual child”—to be coddled and entertained, not respected or obeyed.