3 | THE CHARLATAN'S GAMBIT : A History of the Origin of Politics

Method & Madness | Book III : The Masters' Game

Philosophy is a battle against the bewitchment of our intelligence by means of language.

—L. Wittgenstein

MORES | mores: customs, morals

Morality: a Value-system which underpins personal Social conduct—

The story that we tell about our selves; both to ourselves, and to Other people.

A Morality is a Value-judgement: the truth which we create, and the Value we define.1 A Morality, in other words, cannot constitute an Ethics imbued with the transcendent Value of Absolute-Objectivity—instead, only one composed of an imminent Social-Objectivity.

A morality is a mindset—a worldview.

An Archetypical Philosophy.2

In the far south of Deutsche lands, young forest and rolling foothills give way to tall, snowy peaks. Nestled amongst high mountain meadow—between this and the next lakeshore—was where Nietzsche spent later years of his life, producing an iconic work of social theory: Zur Genealogie der Moral (The Genealogy of Morality). Published in 1887, the Genealogy tells a primordial story of the relationship between Master and Slave; one which fundamentally defines the historical character of human-being.

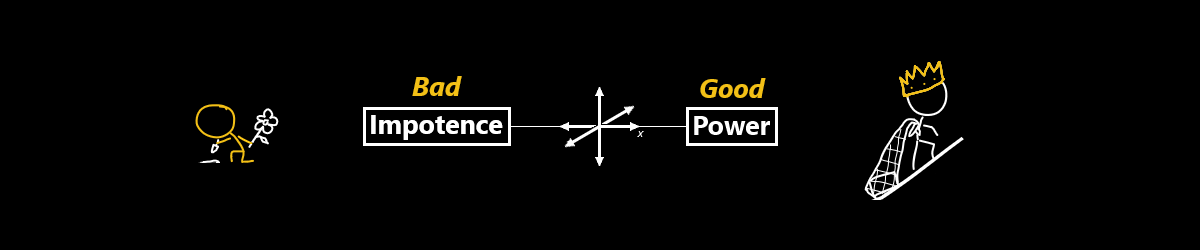

To Nietzsche, Master3 and Slave are mirrored—naturally opposite twin moral archetypes which bound and define one another. The Master is a “Have”4—the Slave, a “Have-not”5. One holds the Power to express his Agency freely over his world and his life… while the other is Impotent, and thus simply does not.

Rich men, Powerful men—men of great success or repute. No matter his disposition or occupation, the Master is one whose needs are satisfied—his stomach full, a roof over his head—and who lives a luxurious existence free from concern for the mundanities of his Survival. His needs are met—therefore, he is free to pursue his wants instead. Holding what privilege is necessary to move beyond his base Survival, the Master is free to expend his Labor instead to further his Prosperity—to live in pursuit of his projects and passions through the exercise of his Agency.

Thus does the Master live a Good life… because he has it Good.

Workmen—whether Bonded or Freed—are those who instead lack these things. The Slave is poor and of meager means—his needs unsatisfied and his existence thus captured by the perpetual drive to stay warm and be fed. His freedom is constrained by circumstance6—his mind not at liberty to consider Prosperity while his body must Labor still for his Survival.

Thus does the Slave live a Bad life… because he has it Bad.

To Nietzsche, Master and Slave are Facticities—opposing archetypes which define circumstance: ways in which the Have and Have-not are dichotomously situated in the world. This situation is not Prescriptive; it doesn’t assign Absolute Value to one or the other morality. Instead, it is simply Descriptive; a story about the way the world is… evidenced by empirical observation.

And so, to Nietzsche, there exist in this world two types of moral systems:

Good & Bad: a Descriptive morality. A system which describes a Socially-Objective7 distribution of Good or Bad situation.

Good & Evil: a Prescriptive morality. A system which prescribes an Absolutely-Objective8 distribution of Good or Evil nature.

Everyone wants to live a Good life. Everyone wants to escape Bad circumstance.

Thus does the Workman wish to improve his own situation. The Have-not dreams of becoming a Have—the Slave, of becoming a Master—so that he could make his Bad life Good, and live free as well in a Prosperous world. To pursue the projects and passions of his choosing, and to expend his Agency in order to fulfill no Other will before his own.

All Masters are made by the will of their people—all leaders called forth through their tribe’s belief. A king is raised to Power through the aggregate choice of the Agency beneath him—by fundamental method of Social-Objectivity.

To Nietzsche, there is Master and Slave… and Priest—

A third man: the “Have-less”.9

Where the Master is Adept, the Priest10 is Charlatan—the Moralist11 instead:

He who covets the Adept’s throne; the ability to command the Agency of men loyal to the Master’s crown. He desires to control the Civil world—to hold in his hand the Power to protect everything he loves. He knows, however, his own weakness best: that he cannot challenge the Adept himself, and must thus work to co-opt the Agency of Civil men instead.

The goal of the Masters’ Game is to achieve Dominion; to cleave from the basal Chaos a world of Order—of Civilization. For the Adept, who holds faith in his Power, the plan is simple: conquest & creation. For the Charlatan, who sees himself as weaker, the plan is single: appropriation.

Thus emerges the Charlatan’s Gambit:

A plan to invert the Adept’s Order: to steal away and reform the Civil world of Social-Objectivity.

Believing that he must resort to cunning tactics to find success, the Charlatan commits himself to a wide array of deplorable acts; any method to bend the Civil world toward his advantage. He conspires in the shadows to convince his peers, betters, and lesser men… that he is, in truth, the most Powerful and capable: that he deserves to be king instead.

And so, the Charlatan makes his first move: the Appeal-to-Complacency.12

To the Complacent does he Moralize, telling them that their situation isn’t actually Bad… but is instead normal; not something to be improved or escaped, but just a natural and default mode of existence. Their Impotence is not a flaw—but instead, a cardinal virtue. They are not poor, but instead meek—not weak, but instead Blameless. Because they’ve never done anything wrong13, they must therefore be right—be Good:

And what isn’t Good… is therefore Evil.

Thus is born Ressentiment: the reversal of base-morality.

Through Ressentiment does the Charlatan move the Blameless to rise as his Righteous14. No longer is the Master’s Power seen as a Good to be pursued—instead, expressions of personal desire and Agency are cast as excess: cardinal vices. Because it is Good to be humble and Blameless (and thus also Righteous to be Good), it is therefore Evil to prioritize one’s projects or seek to improve one’s situation.

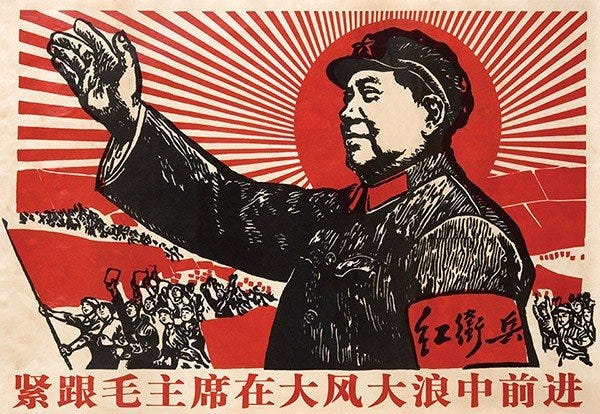

Thus the Charlatan incites the Blameless, arming Eden’s bravest, densest sons—commanding them to rise to his cause to hunt and slay Evil. But by his decree—and his alone—is Evil now to be defined… and thus, does he now define new Evil.

The Master isn’t strong, or wealthy, or free; instead, he is ruthless, greedy, and slave (to his passions, now called vices). Here now—in the Charlatan’s world—the Master’s freedom no longer serves to represent a true freedom… for Capital and Power serve only to enslave, where a Blameless Innocence embodies the ultimate freedom-from-responsibility: to resign control of one’s personal Agency for use by a Righteous cause. This is how Prescriptive systems are cleaved from Descriptive morality—

How Good-or-Bad situation is transformed into Good-or-Evil nature.

Now, the Charlatan makes his next move: the Appeal-to-Nihilism.15

To the Nihilists does he Moralize, moving them instead by confirming their bias—that is, that:

The Cynical believe that the world is a place of natural and inherent Chaos—that laws and morals and “Good” and “right” are but constructs, created by man. They believe that the grand Truth of the Righteous is nothing but a scam and a lie; that the world is—in the end—a place of men lying to men, manipulating everything in a futile attempt to suppress the brute Chaos of reality.

And so does the Charlatan cast himself as the Avatar-of-Chaos, inciting the Cynical to rise—to tear down the false world and reveal the truth: that the world is Chaos, that existence is Absurd, and that the project of Civilization itself will be rendered inevitably devoid of meaning. He tells them what they’ve always wanted to hear: that Chaos is Good and Order is Evil, and is thus able to turn their rage against the Master of the Civil world.16

And here does the Charlatan make his last move: the Appeal-to-Servility.17

The Servile crave what the Master owns—fruits born of hard labor, and the safety of home. Lacking the strength and conviction, however, to simply just take what they want… they choose to bow in submission instead—endearing themselves in hopes that they’ll be permitted to partake of Prosperity greater than what they could’ve achieved alone.

To move the Sycophants to action, all that a Charlatan really must do is convince them that he will be the next Master. Then, when he’s king, he’ll grant them more, and make their Bad lives better—that is, Good.

The Charlatan is the playwright of social contagion: the maker of Ethics, and every ideology. He wages war using moral systems; through obfuscation and deception does he cast himself as PRIMOGENITOR. In this way he claims for himself the unique Power to define Truth and Justice: the exclusive authority to claim knowledge of the truth of Good & Evil.

The Charlatan is the author of dogma; the architect of the system of Good & Evil. Through the Charlatan’s Gambit he moves the masses, co-opting the Agency of Civil and Rival to incite coalition-rebellion. His goal is simple: to install himself as new Master—the leader and liberator of the Proletarian cause. And so, in the wake of their revolutionary action, he seizes his chance to raise his Servile up as an all-new Bourgeoisie, thus-entrenching his Power as Charlatan-King: the Absolute-arbiter to whom falls all judgements made of Good or Evil.

In a world of Good & Bad, the Bad desires to become Good. The Workman is Freed to strive toward Mastery—to live free and well in a better world.18

In a world of Good & Evil, the Good fears being branded Evil. The Workman is Bonded—his ambition, punished—and praised for remaining in his place: already the best of possible worlds.

Nietzsche describes these two systems as irreconcilably opposed: twin moral theories which can never coexist… because one is designed to destroy the other.

Master and Freedman live in tandem: as partners in a Social symbiosis. A tribe elevates its strongest as leaders to better-guide it toward Survival. A Civilization uplifts its brightest to organize Labor and achieve Prosperity. People vest their personal Agency into the competence of Adept-Kings because they hold faith in their unique abilities, and:

The Adept is the one who toils away, building his dream of Eden—of home. But he is just one man alone—and one person, no matter how skilled or able, can only do so much. Thus will he quickly realize that if he hopes to succeed he’ll need allies: followers, laborers, or brothers-in-arms, who would answer his call and lend him their Agency.

And so, if Civilization were a body—and thus, Masterhood its head—the Adept would be the brain itself, and the Charlatan a worm: a brain-eating parasite.

For the sake of its Survival, the worm desires to replace the brain; and so does it inject its poison to persuade the body to attack its own brain. This Ressentiment may convince the body that it is, in reality, Subjugated: that because the brain consumes more Resources and commands all Agency, the body is therefore oppressed and exploited—a body, Slave to its brain. And so do the people—once they feel that their faith has been either lost or betrayed—rise up and turn against their Master, tearing the crown from his head.

An Adept leads and his people follow, for he has proven his worth to them through great feats of competence and Agency. Thus do his people respect his skill, fear his Power, and love his boundless drive and passion—for they know that he works toward their mutual benefit in building Civilization.

A Charlatan leads and his people follow—but in time, they fall away. He proves, after all—time-and-time-again—that his skill cannot emulate the feats of true Mastery, and that he would prioritize his own grip on Power at the expense of total Civil Prosperity. He attempts to cast off fault for his failures, wearing Social-dogma like armor—constructing a world of moral fabrication in which he will never be to blame.19

Thus does he unwittingly invite the garden’s creeping division and decay—and, given time and enough men playing the cunning Charlatan’s Game—its final ruination and return to a world feral, lawless, and free.

For clarity: Nietzsche’s usage of the term “Master” is a fundamentally from mine. Nietzsche’s archetype of “the Master” describes the moral archetype best-suited for Mastery—that is, explicitly the Pragmatist—and not necessarily the person who currently Masters a given civilization. Though similar (and not unrelated), my conception of “Master” is intended to identify the current leader of a tribe, society, or civilization, irrespective of cardinal archetype.

i.e. a nobleman or aristocrat—a Patron or, for Marx, the Bourgeoisie.

i.e. Workmen—serfs, peasants, or the working poor. For Marx, the Proletariat.

As in Sartre & Beauvoir, wherein one’s Agency is constrained by one’s Facticity.

i.e. Empirically observed.

i.e. Theoretically inferred.

i.e. clergy, intellectuals, academics, etc. Any who lay claim to or appeal to the authority of the arcane Power of obscure theory not readily or empirically available to laymen. Alternatively: those who have-less than those who have (-more). For Marx, also Bourgeoisie.

Notably, the Priest can also represent the Egoist—one who is enamored with the Master’s glory—as Nietzsche doesn’t distinguish between the two archetypes within his theory.

Or, for that matter… anything at all.

Once the Charlatan ascends as new-Master, it becomes immediately obvious to the Cynical that they’ve been scammed once again—that the Charlatan was never an Avatar-of-Chaos, but instead a false prophet who’d simply co-opted their Chaos to build new Order. Thereafter, their rebellion continues—their rage against the Master-of-Order now turned against the Charlatan-King.

Politics is the realm of the Civil; War is the realm of the Rival. Thus does the Adept thrive when forced to contend with adversity—i.e. the challenge of Survival—where the Charlatan is adept only when he can play games of intrigue within extant Prosperity.