10 | CRITICALITY: the Dynamic

Method & Madness | Book II : Archetypical Philosophies

The truly-free man accepts the ambiguity of existence—he does not flee from it, nor seek to impose absolutes upon it. He embraces uncertainty, finding meaning in becoming, and acknowledges the weight of his freedom—that his actions have consequences for himself, his world, and the people around him. He is a creator of values, refusing to passively accept tradition as truth, instead choosing to engage in the world and shape it by his understanding of freedom.

—S. de Beauvoir (ab. M. Hise)

All people desire to be correct—all men crave the Power to be free. We learn and grow through our living experience—and, in the end, our stories lead here.

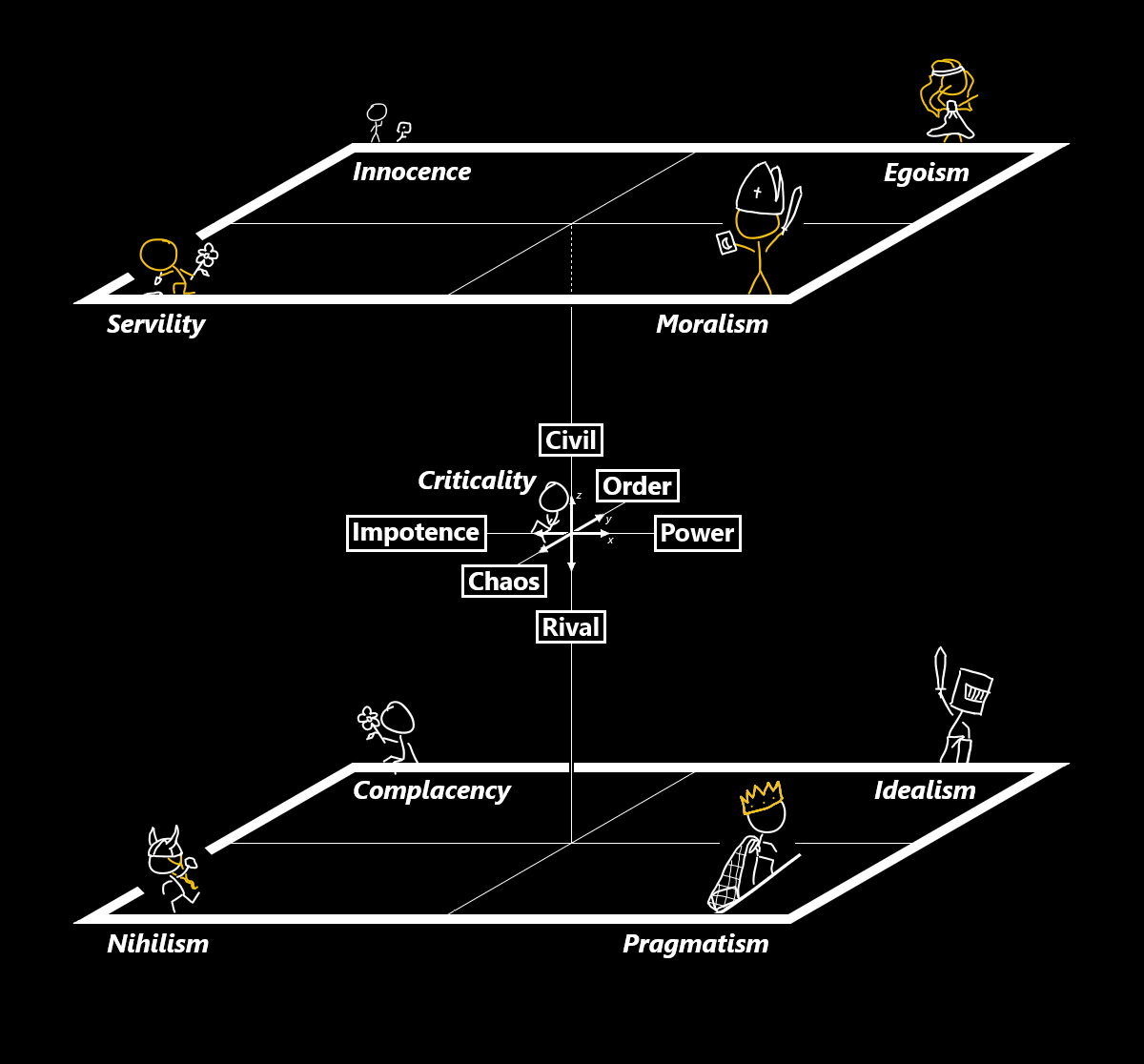

In our hands we hold now an art—a Power—which comes only with a mastery of our Existential science: a Dialectical Cube which contains a brute logic that reveals the moral architecture of any mind it beholds. A structure woven into our Madness—a Method given freely to us through the wisdom of our forebearers.

To Sartre, our fates are our own to make; Man not Being, but first a Nothingness. Man is not a fixed point in spacetime, but is a movement—a vector—instead. A trajectory which lives, grows, and changes—not Object alone, but Subject as well. We have no grand destiny to fulfill, but instead are cast into a world which already exists… while we ourselves remain Ambiguous and originally-undefined—

Not Being, but becoming instead.

Thus do we who have mastered our Madness finally know this—that:

The right method of philosophy would be to say nothing except what can be said—that is, the propositions of natural science—and, whereof one cannot speak… thereof one must be silent.

—L. Wittgenstein (ab. M. Hise)

And so, the Critical is the one who believes that there are two kinds of people in this world:

The stubborn, and the curious.

There are those who make their movement toward the corners of the Cube; who invest themselves wholly in the stories that they’re given, believing that they must place faith in the inherence of a Method prescribed by Man. Then, there are those who travel toward the origin—who know instead that Method is Madness, and thus understand that stories only serve to describe the Ambiguity of existence.

Thus, the Critical is the Dynamic: he who transcends the struggle to find canon, unshackling himself from the weight of dogma through a willingness to reflect upon new knowledge—to reconsider the validity of existing opinion, and to adapt his own attitude to weather and surmount the reality of inconstant and evolving conditions. Unbound by adherence to rigid Absolutes, the Critical possesses the self-awareness necessary to reflect upon his own faults and errors. In this way is he capable of shaping his philosophy; updating his opinions in good faith when he encounters credible new information.

To be stubborn is to be like stone: strong and unyielding in the face of great pressure… until one day the strain grows too great, and the brittle rock begins to crack and break.

To be curious is to flow like water: flexible and Dynamic in the face of obstacles—continuously exploring the Ambiguity of possibility in order to find a new way forward.

Thus is the Critical found at the center, for he is the one who understands that the stubborn are those who’ve discovered some truths—and, thereafter, feel that they must cling on or be swept away, raising them up as sturdy Absolutes to resist the inconstant tide of change. In this way, they can convince themselves of the obsolescence of discovery—that they need sail forth to seek truth no longer… because they’ve already found it. The Critical, however, understands this to be an impossibility; that—to the best of his knowledge, at least—the truths put forth as Absolute-Objectivities are fundamentally inaccessible to Man. For, in the end, are even mountains swept away… but life is born of water itself—

And so, does it always find a way.

Criticality is, by necessity, not an Absolute position.

Criticality is thus, by necessity, not a cardinal Archetype.

Criticality represents a Dynamism of attitude: the understanding that disparate dogmatisms1 spring each from their own kernel of truth—from some-or-other utility within their given situation. As a vector which travels toward the center, Criticality doesn’t imply a complete transcendence of one’s moral bias2. Instead, it implies a mastery of empathy: the ability to understand that, if one seeks to hold an accurate picture-of-reality3 within one’s mind, then one must learn to empathize—that is, to alter one’s viewpoint and imagine; to learn to experience the world from the perspective of any form of mankind.4

It’s difficult for those who feel themselves Impotent to move toward Criticality—after all, to do so would demand that they embrace their Power instead.

To be Impotent is easy—to reject the prospect of Agency in order to resist one’s own responsibility-to-action, denying the reality that one must labor in order to meet one’s desires and needs.

It’s difficult for those who believe the world Ordered to move toward Criticality—after all, to do so would demand that they acknowledge its Chaos instead.

To trust Order is easy—to deny the narrowness of one’s worldview and invest wholly in immutable Absolutes, resisting confrontation with the inconstant nature of a Subjective self and ephemeral world.

It’s difficult for those who think themselves Civil to move toward Criticality—after all, to do so would demand that they imagine themselves judged Rival instead.

To feel Civil is easy—to take for granted one’s place in a tribe, ignorant of how one’s situation would differ if one were rejected and situated outside; denied in-group rights by a broader society.

“By any means necessary” is the Pragmatist’s creed—and so, does he experience the most brittle form of dogma; the least resistance (among others, at least) when approaching Criticality.5 Because his morality is founded upon the necessity of achievement, all that he must be convinced of is that dogma itself is un-Pragmatic: that sometimes—in the real world—it may be necessary to betray his moral bias in order to actualize a project. To commit what he may consider to be distasteful or deplorable acts—acts, perhaps, even simply Evil—in order to accomplish his goal.

After all, it’s the case that—in reality:

One can be both Powerful and Impotent; this, the Pragmatist should easily understand, as he explores the limits of possibility—what is and isn’t within his Power—in the exercise of his Agency in his everyday.

The world is a place of both Order and Chaos; this, the Pragmatist should easily understand, as he is himself the one who fashions Order from Chaos in his everyday.

One can be judged both Civil and Rival; this, the Pragmatist should easily understand, as he knows well how the acceptance and rejection of Others can define his Agency in his everyday.

Dostoyevsky believes Criticality a curse6; that deep reflection and a profound self-awareness destines Man to live a sad existence of unending philosophical torment. In a sense, he’s correct—after all, Criticality is an implicitly destabilizing frame-of-morality. We all, in the end, crave and desire the constancy of dogma—a stable, easy world:

A guarantee of the Absolute reality of a world of constant Order… or constant Chaos.

And so do the dogmatists resist Criticality, averting their eyes and dumbing their minds to the inconstant Dynamism of reality; a tepid attempt in vain to defy fundamental Ambiguity. They struggle against it because they fear change—that, if they and their world exist within an ever-evolving and ephemeral state, then the things which they love could, at an instant, be simply ripped away.7

Thus will any un-Pragmatic Criticality necessarily be an affliction of Sartrean Nausea:

A persistent dread, angst, or anxiety inflicted by an inability to cope with one’s awareness of Ambiguity.

But to the Critical-Pragmatists—you who’ve mastered Method & Madness—the world is yours, for you are the ones best-suited toward acclimation to its nature. You who no longer fear and resist—who needn’t stand upon firm stone in order to pass your Nausea; who are accustomed now to the Dynamic reality of sailing upon the open, rolling tide. You are best suited to live lives of good-faith8, reaching out into the world with curious hearts and jovial minds9—with both the ardent passion and vigor needed to build bright, wondrous new things… and the peace-of-mind to enjoy them.

You who hold our Cube know this:

±x = Agency: I’m capable to act within circumstance.

±y = World-state: Nothing is constant—only given, taken, or made.

±z = Society: I’m judged and defined by my actions.

I am my Agency—the choices in the world which I make.

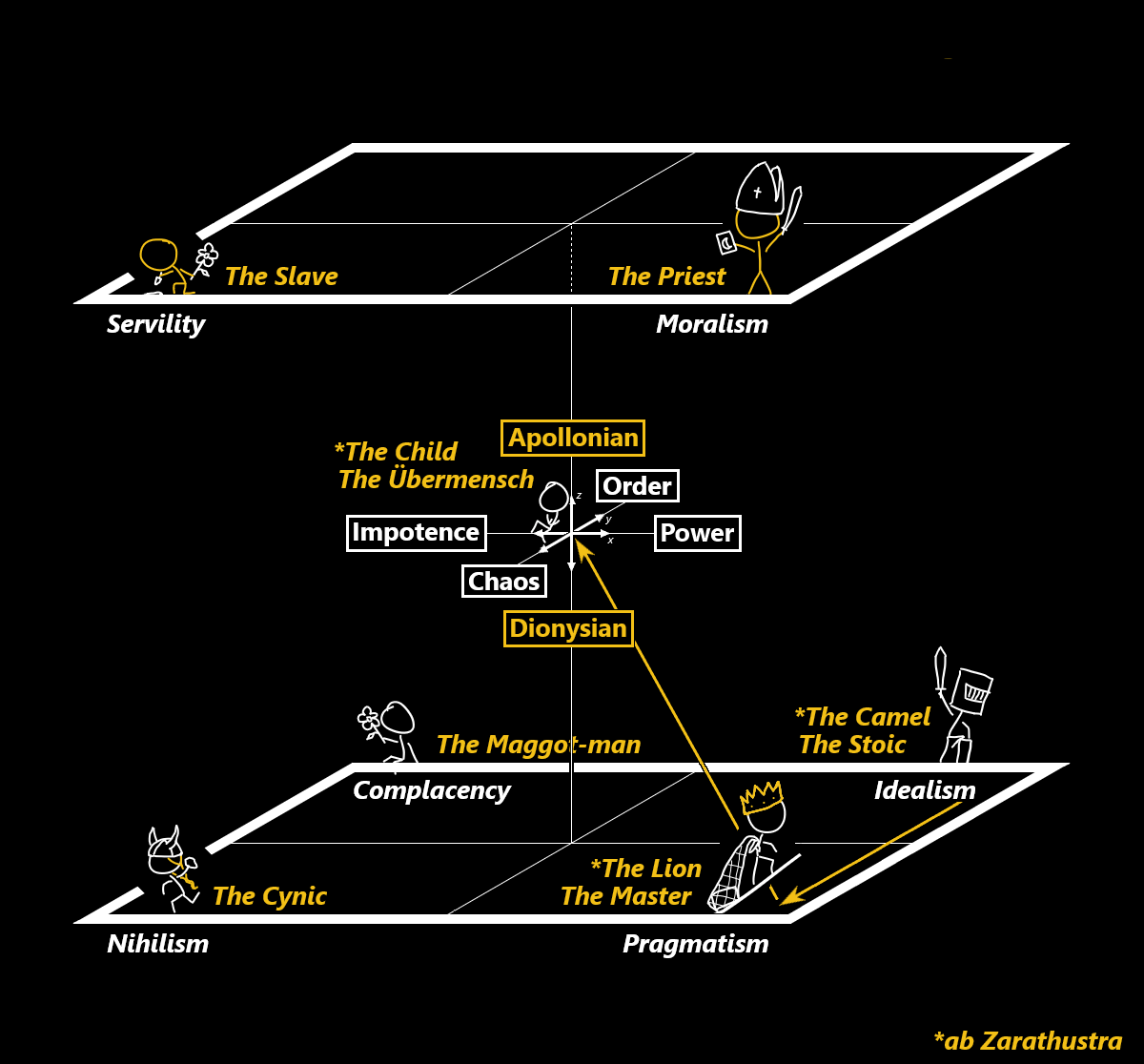

Nietzschean Archetypes

Nietzschean archetypes are distributed broadly throughout his various works. As would be expected of his potent and free-flowing style of poetic-prose, it can be difficult to see them as logically-distributed and chartable… at least, until you read Beauvoir.

In his work, Nietzsche appears to omit the attitude of Egoism—merging Egoism instead with Moralism in his archetype of the Priest—due to his specific focus on the dichotomous split between Apollonian and Dionysian moralities. He holds both in combined disrepute against the attitudes of the Master (the Pragmatist) and the Übermensch (the Critical).

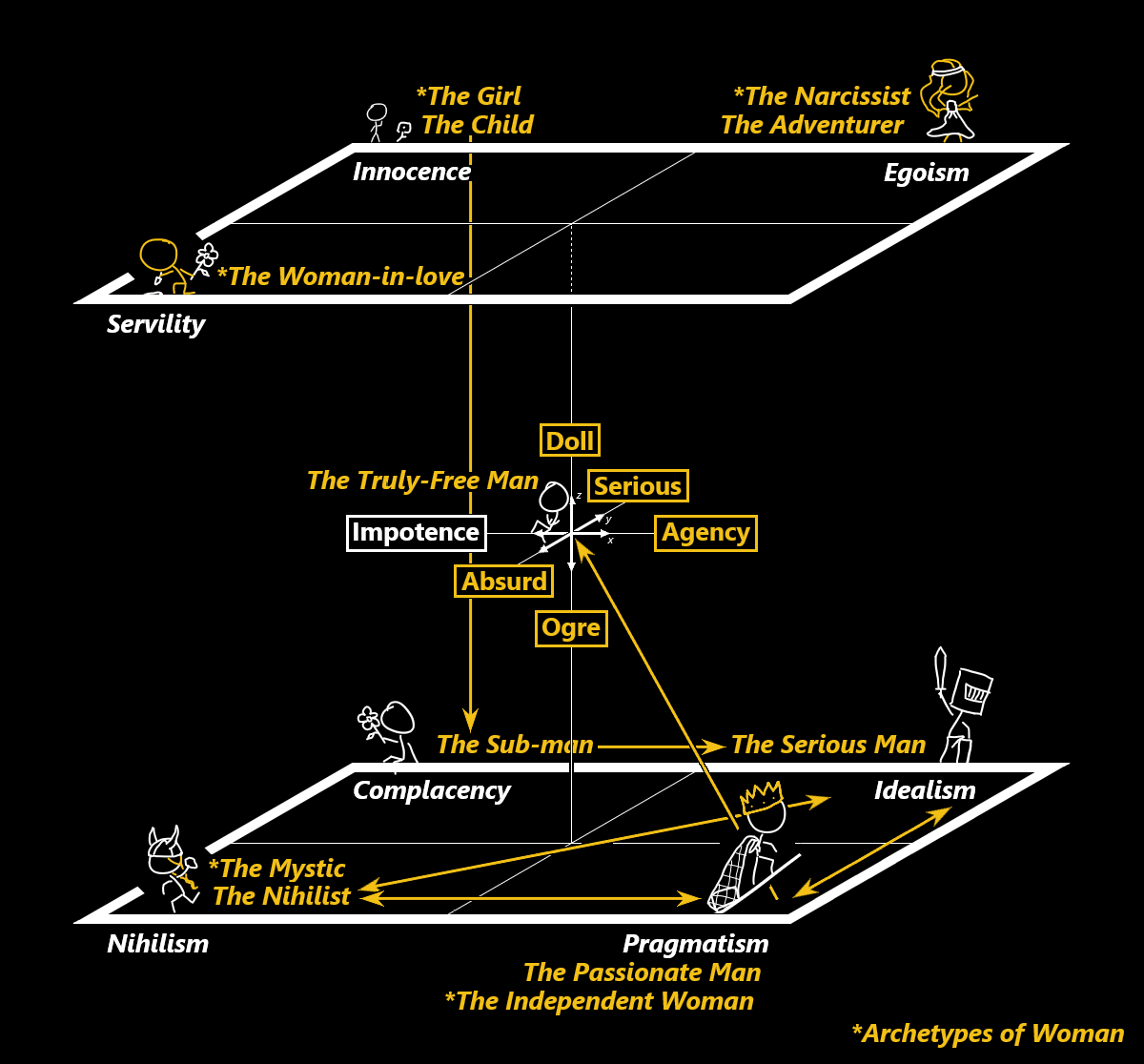

Beauvoirian Archetypes

Beauvoirian archetypes are concentrated narrowly—the Archetypes of Man laid out as an explicit progression-of-attitudes within The Ethics of Ambiguity, and in The Second Sex the Archetypes of Woman described as the product of a reactionary clash between Woman’s Agency and Facticity.

In her work, Beauvoir appears to omit the attitude of Moralism—merging Moralism instead with Pragmatism in her archetype of the Passionate Man/Independent Woman—due to her (and Sartre’s) specific focus on the dichotomous split between Serious and Absurd worldviews. Thus, while she decries all dogmatic attitudes, she demonstrates specific contempt for Adventurism/Narcissism (the Egoist).

Philosophy: a mindset. a worldview. The way that one chooses to see the world, and thus approach living one’s life.

Αρχή | archí: origin

Τύπος | týpos: form

An Archetypical Philosophy is the logical basis of a person’s attitude, derived from observation of how he-or-she chooses to exist.

The dogmatic are the stubborn: those who entrench within their corners to resist fundamental Ambiguity.

i.e. one’s base-corner or cardinal Archetype

As in Wittgenstein.

Other people—Other Subjects—are a part of our world and reality. Thus, if an individual cannot account for the mindset of Others, then he can neither predict nor understand their action—and, therefore, there’s a sense in which it’s only possible for him to hold a loose grip on Facticity; an inaccurate picture-of-reality.

A dogmatic-Pragmatist possesses the modes of [Power/Chaos/Rival], and is thus the only Archetype which need not struggle with one of: Impotence, Order, or Civility.

Wherein "Pain and suffering are always inevitable for a large intelligence and a deep heart. The really great men must, I think, have great sadness on earth."

This is explicitly not an Absurdist statement, as the Absurdity for which Camus advocates is definitionally Absolutist. To Camus, Chaos is real and Order is fake—however, the reality of Dynamism is that our world is one which hosts a convolution of Ordered and Chaotic states.

As in Sartre—i.e. true to oneself and to reality; the opposite of bad-faith. As in “an act of good-faith”.

As in Nietzsche, wherein The Gay Science is “Die fröhliche Wissenschaft”, which can also mean “The Joyous Wisdom”.