The Contemplation of Happiness | Dipping Your Toes into Existentialism

an Essay for the Modern Existentialist

0 | The Specter

Alone. Alone.

You and I are each ever alone. That is what sets us apart. That is what binds us together.

We are the only ones who will ever see what we see—who will hear what we hear. Who will ever feel what we feel and know what we know.

I am the only me.

You are the only you.

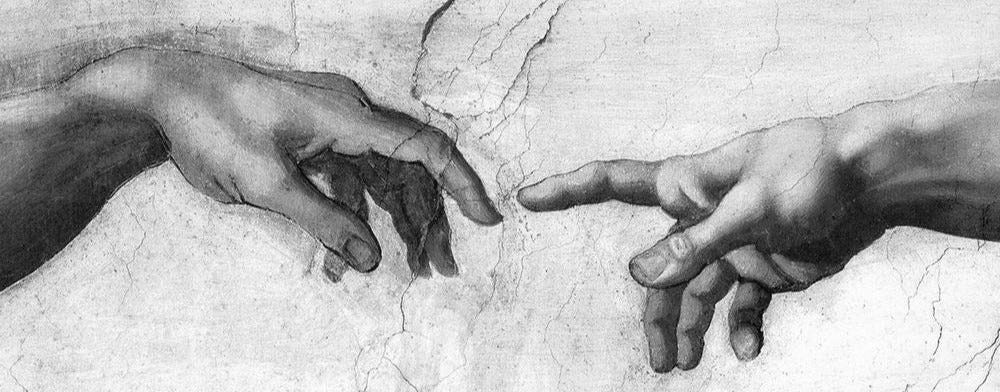

In this, we are together—together, in our isolation. Removed from one another without recourse, as islands set adrift upon a shimmering sea. Held apart for all eternity by a vast expanse of water; by experience, appearance, perception… and the difference which spans ever between us.

Context is important. Context defines all things. Nothing exists without its context. Without a context in which to exist, a thing cannot mean… anything.

I spent most of my formative years unhappy. I felt constantly alone, keenly aware that I stood apart; that the questions which possessed my every waking moment drew no concern from my peers. A specter of gloom followed in my wake, blotting out the sky. It cloaked me in a thick, oppressive mire of angst—of discomfort with the human condition. It gorged itself upon the inklings of mortality—thrived upon thoughts of a futile existence. With each inch of me that I lost, sunk deep into that mire, the specter stole another piece of sky.

I spent years grappling with this question:

How could anyone stay happy after realizing that everything that they’d ever do would ultimately amount to nothing?

That nothing anyone could ever do would be lasting; that everything fades, crumbling again to the dust from which it came. I suppose that, at some point, I realized that most people just don’t think too hard about it—whether they’re just… tepidly unaware of the question, or whether they just try their best to ignore it and put it out of mind.

That was it, then. In those days, “not really giving it much thought” was what being human meant to me. The essence of humanity was ugly—to be shallow, unintelligent, and lacking of purpose. To ignore the important questions, and to obsess over and invest in something or other that someone else told you would lend your pitiful self meaning. And, I grew to hate it—to hate the absence of meaningful consideration. To hate the futility of existence, and thus the idea of humanity itself.

None of the people in my life ever had an answer for me. Most still don’t today. But… I did manage to find one anyway. Somewhere along the way, I managed to work up enough grit to claw my way out from the bottom of that murky mire. To turn and face that specter of gloom, and to embrace it with a smile. I could never outrun it. I never did outrun it. After all, a specter is just a ghost—an apparition which had, once upon a time, been the deepest part of someone’s soul. And this one...

This one was mine.

On that day, what I told myself was this:

If nothing matters, then it shouldn’t really matter so much to me that nothing matters. Right?

From where I stand today, I can only describe that phrase as… clumsy. Inelegant. Utterly lacking of the poetic finesse which I’ve grown so proud to call my own. But it was a makeshift solution, after all. Something I’d found when I was grasping at air—when I would’ve been willing to dig my nails into anything that could’ve pulled me out. But in that moment, I was so very proud.

I was proud that I could finally tell myself that it was okay to be happy. For the first time since I’d been a child…

It was okay to be happy.

Not too long after I first came to this realization, I picked up Nietzsche for the first time. It was electrifying. I read, and I read, and I couldn’t help but laugh. How many years had I squandered thinking that I was different? That I stood alone? That I should try to be something other than human in order to glimpse a chance at being something more—something better?

And yet, here he was. A like mind—a kindred spirit… standing tall in the light of day. Every single inch of him—body and mind—human, all too human. Loved and maligned, misunderstood and fallen to insanity, he’d beaten me to the punch by over a century. Next to him, I was nothing—a pale imitation. A child, standing at the toes of a giant. How naïve I must have been to believe I stood alone. How arrogant I was to think that I was special.

Herr Nietzsche, The first lesson that you ever taught me was not that God is dead—for that, I learned in my own time. What you taught me was this: that in the wake of fallen idols, humankind has had its freedom foisted upon it. In the shadow of the dead gods, we must walk free... for there is recourse no longer. With great affection, M. Hise

1 | Faith and Fantasy

Seeing is believing.

You believe what you see. You see what you believe. You believe that what you see… is.

Your world is always as you imagine it. Your world is only as you imagine it to be.

Your world as you imagine it is just this: an imagination.

Your world is a fiction—a fantasy, fabricated of information gleaned from a reality which may only ever be perceived. A reality which may never be known.

The human being is incapable of accessing objective facts of reality. That is because the world is, as Arendt has said, to the human individual only ever as it appears to be. You and I can never experience what we would conceive of as being truly real. We will only ever see what we see, hear what we hear, touch what we touch. Thereafter, each and every one of our observations is just this: a fabrication, founded on sheer faith and fantasy—built upon what appears to be.

Imagine the colorblind man, who has always existed in a world entirely absent of the color green. How would you go about explaining to him what that green might be? Would tell him that it’s the color of the grass, and the trees? How should he understand what you say? How should he ever come to know what it is to see the color green? How could he even begin to imagine a color which he has never before seen?

Now think of you as yourself: an individual who exists in a world in which there are all of your familiar colors—colors which you know and see. Imagine this: that there might be many more colors out there in the world, just beyond your reach. How would you know if there are any? Could you conceive of a new color, of which you and I are incapable even of imagining?

Our perception is focused through the lens of our biology. We must always gaze through this screen, for we have never known anything beyond it. We are incapable of truly comprehending what it means for there to be something beyond it. We cannot begin even to imagine what kind of experience would exist in such a place—and that inability is, in itself, part of what it is to be human.

To be (that is, to exist as a human being) is to live by faith and by fantasy. To glean data from appearance, constructing for ourselves each our own inner fiction—to believe that the reality which one perceives is truly real of itself. It is at once to live in the state of believing only what one perceives, and also of perceiving only what one believes.

If, however, we thus declare each person’s inner life to be composed of just sheer fantasy, it must also be made abundantly clear that that same fantasy must—for all intents and purposes—therefore constitute each individual’s internal representation of reality. If we cannot perceive reality—if, to us, nothing can be truly real—then the un-reality with which we are left is what is our everything.

Our respective realities.

Fact and fiction—fantasy and reality—are seamlessly woven together. Together, they are your one.

Together, they are your everything.

2 | Magic

When we were younger, the world appeared to us to be a much more magical place. It was filled with imagination—discovery. Possibility in everything. But most of all, with meaning and purpose—inherence, woven into all things. I remember the many adventures I had—donning a mask to fight evil in the streets. Whispering magic spells and slaying foul beasts. Exploring new, uncharted worlds, as far from home as I could be. Saving the girl I liked from some strange, contrived travesty. I remember being afraid of the dark—terrified of the ghosts and monsters that I knew with the utmost certainty lurked just beyond that ashen veil.

All of this… because I did not yet know.

Because we did not know—because we were young and freely unaware—our minds did as they often do. They played, and they imagined. They spun tales and breathed life into our fantasies, filling in the gaps where knowledge was absent—weaving new stories and forging new answers to questions outlandish and unknown. They spun and conceived, concocting strange solutions to the myriad mysteries which stood beyond their comprehension’s edge—all of this, by faith and fantasy.

When I was younger, my world was filled with possibility. But, as I grew, so too did my understanding of my place in a world which had never belonged to me. I did not dream as much as I used to. I did not hope so much as I had. My faith in the world which I saw was tested. I watched as my fantasy began to crack and to crumble, beaten down by wave after wave of new knowledge. And, as my world crashed and broke against itself time after time again, a new fantasy would rise as the old would fall, ascending to take its place.

Max Weber refers to this phenomenon as the “disenchantment of the world”—the loss of that shine, and that mystical gleam. The slow disintegration of that cosmic reverence with which people of bygone eras had looked upon the world—of the idea of the presence of inherent purpose in the act of living and dying. Of the guiding hand of a cosmic force which would lend some innate, ethereal meaning to one’s continued existence. Of that kind of wonder and fascination with which a child might still approach the world of today.

Weber describes such a world—one which yet holds fast to a mystical, innately meaningful visage of reality—as bearing the character of an “enchanted garden”. Beauvoir, I think, might be quick to conceive of the denizens of such a garden as sub-human; as unworthy of the respect which should be afforded to a free-and-equal human being. I think, instead, I might simply prefer to call them children as well.

The world which exists in the time before this revelation—this “enchanted garden” of Weber’s—dims in the face of modern sensibilities. The garden through which we walked as children has long-since faded, now overgrown and lost among the thick brush and the trees. We may search for it, seeking to reclaim the lost days of our youth—pining again for the chance at possibility. We may yet see the children who walk among us, who have never lost sight of that garden—who never lost their faith, and who see still that old, enchanted world. But once our eyes have drifted from it, we may never again reclaim it. At least… not without telling ourselves one great, magnificent lie.

That is what it means to say that God is dead.

God is dead. … And we have killed him. How shall we comfort ourselves, the murderers of all murderers? What was holiest and mightiest of all that the world has yet owned has bled to death under our knives: who will wipe this blood off us? … Is not the greatness of this deed too great for us? Must we ourselves not become gods simply to appear worthy of it?

3 | Freedom

When it comes to the theory of existentialism, there is a pervasive cloud of misconceptions that tends to obscure the heart of the philosophy to the minds of those unfamiliar. This missed impression soaks it through—weaving itself between its fibers, filling every pore—until the very act of even reflecting on the nature of our existence appears to become something ghastly; hideous and sickening, toxic to the mind. People unfamiliar with existential philosophy tend to believe the discipline to be some kind of “philosophy of darkness”—where troubled minds go to be troubled minds. They think existentialism a cynical defeatism—a school of thought which would lead its students to lose sight of purpose in living and dying, and thus to surrender themselves to a host of grim sensibilities. They equate it with nihilism—with the rebellion of troubled teens, and with a spiraling plunge away from the light of all things good and sane.

It appears to me that, in general, these assumptions and beliefs are formed upon a set of shallow preconceptions—upon second-hand or second-rate information. Indeed, in his unfamiliarity, the common man is disposed to believe the existentialist to preach a hopeless, meaningless, fruitless existence; one in which nothing can truly be accomplished. That we—the human race—should just sit around and mope and die because none of it means anything anyway.

When framed in such a fashion, it’s only natural that one’s immediate reaction should be a kind of violent rejection—after all, what kind of person would willingly choose to invest in this kind of philosophy? People want to be happy, after all—and I, at least, have never seen how such a nihilistic attitude could ever lend itself toward achieving that goal.

Existentialism… is not nihilism.

It is in reality a great injustice to conflate these two schools of thought, for they are—in truth—the most bitter of mortal enemies. Existential theory has never concerned itself with the contemplation of a meaningless existence. It has always, instead, only ever been concerned with the lack of inherent meaning in existence—and thus, with how as mortal men we might be able to move forward after coming to that understanding.

Existentialism is not the place where troubled minds go to be troubled minds. Existentialism is instead the place where troubled minds go to seek salvation.

The state of mind which is conducive to suicide is not necessarily one of mental illness. More fundamentally, before we even reach that point of discussion, it is first one in which the appeal of the acts of living and dying have been reversed.

Life is joyful. It represents possibility and opportunity. So long as you live, after all, there exists yet still infinite potential. Many things may still be experienced, and many things may yet be found to be pleasant. Thereafter, death represents the disappearance of these things: the final evaporation of possibility.

Whenever such a time comes, however, that the appeal of life begins to fade, the prospect of death shall become all-the-more alluring. Even when life has lost its joyful luster—even when it no longer offers the promise of pleasure and possibility—the meaning of death shall remain ever-constant. When life promises no more joy—only tears and struggle and strife and pain—death still offers what it always has: the evaporation of all things. Death stands forever fastened in place: the only permanent fixture by means of which one may seek to attain freedom from life. To one whom life denies new possibilities, death represents one final novelty. The potential to discover lasting peace—one final, eternal release.

To Camus, suicide represents the most fundamental of philosophical questions: one which must be asked and answered before any other may come to mind. What, after all, could be more fundamental to the nature of human existence than the simple question of whether or not we should continue to exist at all?

With respect to this question of suicide, Camus makes the assertion that there is no logical correlation between it and an affliction with a meaningless existence. Why, after all, should the simple fact that you have no reason to live… mean that you should die? Does the simple fact that nothing motivates your existence mean, somehow, that you should stop existing? And, if you should deign to answer that question with a yes, then I would ask you to answer the next, paying careful attention not to pose an argument of circular logic:

How… and why?

Once you’ve reached that point—the point at which you’re willing to cast away your life—is there really anything left in the world that you can’t do? If you were willing to commit yourself to death—to surrender everything you are and could be in exchange for a chance at eternal release—then what power on earth could be left to constrain you? What is it that remains which could prevent you now from rising up against that pale, bleak world—that could stop you from waging rebellion against it and seizing for yourself everything that you believed could only exist in your wildest dreams?

If nothing matters, then it shouldn’t really matter so much to me that nothing matters. Right?

Shouldn’t that discovery be… exhilarating? The realization that nothing in the world could ever hold you back again?

What Camus offers us is a taste of the ultimate freedom: the understanding that existence is, in itself, nothing but a sheer absurdity. He offers us freedom from hope—from having to strive toward some distant, unreachable ideal, and from seeking the things for which we have always been told that we should be seeking.

Freedom from ourselves… and freedom from everything.

4 | Will

History tells us that both Sartre and Camus considered completely ridiculous the fact that the whole world sought to label Camus as an existentialist. He was, after all, strictly not one—for instead, he was what is called an absurdist.

There is a sense in which these two disciplines can be thought of as being quite similar, as the subject matter in which they deal is essentially the same. Where they differ, however, is fundamentally in the way which they choose to redeem the idea of a meaningless existence to the student of their own philosophy.

Existentialism, as I have previously described, is characterized by its fundamental concern with the idea that there is no inherent meaning in existence. Thereafter the claim can be made that, because meaning is not inherent to the nature of man, the human individual is afforded instead the opportunity to create it for himself—to forge his own path forward in search of meaning in the project of living.

Absurdism, in contrast, dictates that there is no meaning in existence—no way to ever create it, and no way in which it may ever be found. This, to the absurdist, is nothing more than an immutable fact; an inherent property of the human condition. That is what it means to say that existence is absurd: that the human animal is driven to find meaning in a world which is cold and empty of it. That we must seek—but, from the beginning, were fated to never find.

Thus, it appears to me that, if given some thought, it becomes clear in the end that the absurdist and the nihilist are in reality just two faces of one in the same coin. If the individual chooses to accept this idea of an absolutely absurd existence, then that individual will find himself sat immediately upon the coin’s edge. There, he will be liable to being tipped over, toppled easily onto either face—made to channel his energy into the world with either malice or with laughter. He will act upon the world with either wrath or with joy—this, by choice of what amounts to random chance, and by the fickle whims of the individual.

Nihilism is a fundamentally dangerous philosophy. Like absurdism, it teaches its students that there is no meaning to be found in life and living. Practitioners of a nihilist philosophy tend to think themselves pragmatists instead—realists who understand the true and meaningless nature of an absurd reality; who are liberated and freed of the delusions which mar the minds of lesser men. Nihilists are encouraged, thereafter, to gorge themselves upon hedonism—to take without restriction whatever action it is which they find most interesting or appealing. Because nothing matters—because everything crumbles to dust in the end—you may do whatever you think feels best with no consideration for consequence; for the humanity of the Others or the reality of the world which exists all around you.

Thus, though nihilist-absurdist philosophy sanctions all the freedoms of which one could ever dream, they also equally sanction every atrocity. From slavery to sexual predation—from oppression to nuclear holocaust. Vivisection, cannibalism, crucifixion, dismemberment, mutilation…

The list goes on, for nothing is forbidden. Anything and everything is permissible, so long as you desire to make it so.

Nihilism is that “philosophy of darkness”—what people fear when they hear it said that God is dead. For if God is dead, then who will guide us? Who will show us the way? If God was good, and everything that was good was of God, then what remains for us in all the world but evil?

I think, perhaps, that in isolation, absurdist philosophy would be rather harmless—well-enough left alone to its own devices. But ultimately, the fundamental problem with absurdism is that it doesn’t exist in isolation. In the context which it exists—that is to say, within our world—it appears to me that Beauvoir must stand in the right when she rebukes Camus, rejecting his philosophy as far too close a cousin to sheer nihilism.

I think that I’ve always really wanted to believe in Camus. It speaks deeply to my poet’s heart to dwell and thrive within the absurd. To live in that state of constant contradiction, and to rise in revolt against what binds me, knowing that I must lose—that I will always lose, time and time again—but still, to struggle onward. It seems… romantic. Whimsical. To cast humanity into a place where we each must choose whether we will play the tragic hero or the ascendant villain upon that great stage of life—but once, only once, before the final curtain drops.

But alas, to the existential thinker here, the nihilist-absurdist position reveals itself to be irredeemably flawed at its core. It has a pretty face—complete with all the bells and whistles—whispering all the right honey-sweet words to capture and enfold the troubled mind deep into its fantasy. But it feels like it’s missing a piece—like there’s a logical leap lurking somewhere deep within its logic that I just can’t quite stomach. Perhaps it feels a bit like a leap of faith—an appeal to emotion or aesthetics when Camus asks us to trust him in the face of Sartre’s appeal to the rational mind.

Funny, isn’t it? That I would have qualms with trusting faith over reason at this point.

The question I would like to ask Camus, if I could still today, is this:

Why should an individual choose to rise in revolt against the absurdity of the world? Why should we choose a path of social responsibility—of giving a damn about anybody else—when we’re faced with a choice between that and the pure, unadultered hedonism which nihilism promises so freely?

And he would reply, telling me that I would rise in revolt because I want to—not for anybody else’s sake. And I suppose that, in my case, he might be right. But I think, however, that Camus has not accounted for just this one thing—that not all minds are like his or mine. I haven’t enough faith in humanity, I think, to believe that any great number of men or women or children of this earth would choose to walk a path of revolt when they could instead simply elect to embrace their baser instincts. When they could spend their lives and their time on this earth seeking pleasure after hedonistic pleasure; again, and again, and again.

In the end, one could say that the absurdist is no more than just the happy nihilist. And, thereafter, one could just as easily say that the nihilist is naught but the angry absurdist. The line is blurred—the distinction poorly defined. At any instant—any random point in time—one could just as easily fall to nihilism as one could rise to champion the absurd mind.

If I recall correctly, Sartre said something of this nature:

Man is impaled upon his agency.

Or, more popularly (and rather more mundanely):

Man is condemned to be free.

To be impaled upon your agency means that there is but one thing in this world over which you have no power to decide—that is, in that you must always decide. You are always an agent—always in control, and always responsible for the actions which you make. For they are your decisions, made under your discretion, always by your own will and mind.

One of the most common objections made against this assertion is that there is no conceivable way in which man may have the ability to choose his own circumstances. But that’s beside the point—that’s not what this is about. There is no claim made as to whether or not man has the ability to choose his circumstances. Rather, instead, the claim which Sartre makes is that, in every given circumstance, man still has the ability to choose. Regardless of the context of any given situation, the individual still must make a choice.

Take the example of the chronically sick man—he, who has no choice in his situation. It isn’t as though he has the opportunity to choose whether or not he gets sick. That is not his choice—not a function of his agency. He does, however, always have a choice in the way he reacts; in how he chooses to deal with his sickness. He may choose to improve his general hygiene in hopes that he may become sick less often. He may choose to medicate against it when a bout does strike him, in hopes that he may recover more quickly. Or he may choose to lie down and give up, simply allowing the illness to run its course. All of these are choices—choices which he must make.

Let’s say, then, that this man suffers from a more acute sickness than he had initially imagined. It infects his brain, sending him to the hospital. There the doctors inform him that, due to this unforeseen illness, he has become a quadriplegic. In this matter, he did not have a choice. He did not get to choose or decide the severity of the illness that afflicted him. But still, confined to the prison which his body has become, there are choices which he must yet make. He could choose to give up and surrender to the illness, wallowing in misery as his body wastes away. Or, he could choose to cling to hope—hope that one day medical science might become able to cure him, and he could return to his life as it was before. These are both choices—choices which he must make.

Rather cheekily, Sartre makes the assertion that, even if you were to choose not to make a choice, you will still have actively made one anyway:

The choice to not choose.

We are condemned to be free. Make a choice for yourself—for, if you do not, no one will do it for you. Do not shy away from your freedom. Do not allow anyone or anything to deceive you into thinking that you have no will to act. Give your life its own meaning. Breathe that life into your fantasy. Take heart, and have faith—for fantasy and reality are your one.

Together, they are your everything.

5 | Choice

I’ve always found Sartre’s philosophy—despite how he might deny such claims—to be characteristically bourgeois. It’s high-brow; targeted at an at-least moderately well-read population… if not at a highly educated one. For this, however, I do not hold him at fault. After all, that’s ultimately what must be done to gain attention within academic circles.

The practice of philosophy (among other academic pursuits) tends to demand the exercise of great intellectual rigor—of a higher order of thought. To really commit effort to reading and understanding—which, admittedly, I often find myself loath to do. But, in spite of these considerations (or perhaps more as a result of them), the philosophical nature of Sartre’s works makes them all-the-more inaccessible to his intended audience—to the proletariat of the world, and to the common man.

The “spirit of seriousness” is something with which Sartre and Beauvoir concern themselves extensively. They characterize it as an attitude which regards the world as holding some kind of inherent or objective meaning—this, in spite of the fact that it is absent of any of such thing. They describe it as the misguided belief that actions made within this world hold any kind of transcendent weight of importance—divine or not—which may or may not exceed the bounds of our world and our experience. Like the children, who walk Weber’s enchanted earth—who imagine their existence seriously.

Beauvoir put it best when she said that we, mankind, are abandoned upon the earth. We are alone; left to our own devices. When we come to realize that there has never been any transcendent path or guiding hand of truth which stands to light our way—when our world loses that enchanted shimmer and we finally arrive at the understanding that each our worlds are shaped to fit each our own fantasies, we fall either to despair—to that “philosophy of darkness”—or we rise to take hold of our freedom. To forge our own truths and blaze our own paths, by the power of nothing but sheer faith and fantasy.

Beauvoir was not strictly a philosopher—or, at least, she didn’t think herself one. She imagined herself a political scientist—and she was a damn good one at that. And, as a political scientist, Beauvoir was fundamentally concerned with the state of the world and the people who reside within it. Where philosophy can often seem abstract and aloof—detached and unrelated to the world in which we live—Beauvoir brought her and Sartre’s ideas crashing down to earth with the ferocity and eloquence which can only be expected of the woman whom many consider to be the founder of modern feminism.

To Sartre, the process of finding meaning in a world in which it is not readily provided is actually quite a simple task. What he says, essentially, is this:

Just make your own.

To Sartre, life is about projects. Finding things to do which interest us—tasks which we would willingly take on, and to invest our lives toward the pursuit of their progress and completion. It could be a personal dream: to become a chef, or a pilot, or a famous athlete. It could be something grand: to save the world from impending doom, to conquer it by might or money, or to be the first man to set foot on a new one. It could even be something mundane: raising a dog, caring for a garden, falling in love with the man or woman of your dreams.

It could be just to be happy.

Your projects could be anything at all—so long as you believe that they give your life meaning.

We are who we become.

…Or something like that.

6 | Reality

At this point, however, it appears that the true difference between the nihilist-absurdist and the existentialist may not yet have been made fully clear. In the end, after all, doesn’t this dichotomy of meaningful and meaningless existence seem to boil down just to semantic play? Both philosophies preach personal freedom. Absurdism tells you to chase your interests and your passions—to go and do whatever you want. Whatever makes you happy.

How is that different from a Sartrian project?

The answer here lies in a disparity in attitude—in a contrast in the way which the scholar of each philosophy will choose to conduct himself with respect to the Other. In the connections which he makes with the other individuals who exist in the world all around him.

Absurdist philosophy makes it easy for the individual to disregard the Other as inconsequential—as an obstacle which hinders the achievement of his goals, or as the object of a zero-sum game which is to be played and then to be won. He holds the Other in such contempt, thinking only of the realization of his own desires, all-the-while failing to recognize that the value which he derives from his victory comes only through its acknowledgement by that very same Other. Camus, of course, would not characterize his own philosophy in such a way. These are bitter words—words of rejection which belong to Beauvoir. Camus, however, never does address this criticism, and I myself have never been able to find a satisfactory reply.

In the end, the most basic flaw which pervades the essence of nihilist-absurdist philosophy is this: that it may only exist in isolation. It ignores its context—the reality in which the living, breathing individual resides. One could say that, in a sense, when the nihilist-absurdist gazes out into the world, he sees only nothingness; only his self as something real, alone in all the world.

We, as human beings, do not live in each our own vacuum. We are not individuals by ourselves. Indeed, in the first place, if there were no Others to stand apart from our selves, then the idea of a self could not mean anything at all.

As human beings, we are only truly human when we are a we—when we are together.

You and I are social animals. To crave contact and companionship is hardwired into the very fiber of our beings. We function in a manner which we would consider typically human only when we have had the opportunity to live in the company of others—as people only when we have been among people. Sartre has said that the gaze of the Other fixes us into facticity—in the existence which we share with one another, and what is popularly considered reality.

A man decides one day that he is fed up—tired of living his monotonous modern life. He packs his bags with essentials and leaves, walking down toward the docks. He hires a local fisherman to take him to one of the many uninhabited islands off the coast. There, he will become a hermit and live the peaceful, solitary life of which he has always dreamed. When at last he arrives upon that island’s shore, he says this:

Ah… I am alone at last.

One could say that the hermit is free to make this choice. That his chosen project may be considered eccentric, but that to abandon society is well within the scope of his free will. He may not in good faith make the claim, however, that in choosing to abandon society, he now exists alone in all the world. While it may be true that he has forsaken his continued involvement in society, it will never be the case that, by simply deciding to leave a social context, he will no longer suffer its influence. For he was born to a mother—grew up alongside others. Even if he never had any friends in the world, he still spent years in full view of people being people, and for all those years of his life he will have observed behaviors and acquired knowledge, internalizing everything he has ever seen and heard as a fundamental part of his being—learning, as human children do. For all his life, he was afforded social contact, and that is what made him human. Thereafter, no matter what choices he may make, nothing he does may ever make him anything less than the human being whom he has become.

But if we stop for a moment to consider… doesn’t that seem like a ridiculous assertion? After all, are we not all human by birth?

It’s obviously not debatable that we each possess human biology at birth, and that makes us each human in a sense. However, I would argue that, in another sense, we are not—for human biology alone does not confer upon us all the characteristics to which we would ascribe our innate humanity. What makes us us—what shapes us, and what distinguishes us as human—is our actions, our projects, and our experience. Our interactions with one another, and the way in which the gaze of the Other fixes us within a common reality. As Sartre has said:

We both are and are not who we have been, and both are and are not who we may become.

One could say that biology does not make us human by birthright. What it does, instead, is confer upon us our fundamental potential to become human.

In the 18th century, a feral child about the age of 12 was discovered roaming the forests of southern France. Today, he is known as Victor: the Wild Child of Aveyron. When he was found, he was unclothed—his body covered in scars and callouses, his tongue unable to form words. Rather than being mute, it was discovered that he had simply never acquired the knowledge of speech. These factors led researchers of the time to conclude that he had lived alone in the wild for the vast majority of his life. Indeed, it appeared to one medical student of the time—Jean Marc Gaspard Itard—that, when he was discovered, Victor resembled less of a man than a beast.

Itard went on to adopt Victor into his home upon the premise that he would “civilize” the boy—that is to say that he would teach the boy to be human. He clothed the boy and cut his hair—made him up to look like a young man of the time. He began to instruct Victor, attempting to imprint upon him the two traits which Itard believed made human beings human—two fundamental characteristics that separated beast from man. For Itard, these were language and empathy; the two traits which allow the human individual to exist in the company of others. Two traits which we today would consider quintessentially human.

In the end, Itard was unable to “civilize” Victor. While Victor did display some progress in the acquisition of empathy, the boy was essentially unable to acquire or understand language to any meaningful degree. Itard would eventually come to consider his work a failure, leaving Victor in the care of an older local woman. There, Victor would live out the rest of his life, dying of Pneumonia at the age of 40.

Feral children are broken. There’s something critical absent from who they are; something which cannot be recovered, for it was never there in the first place. Something that, when denied to them, seems to strip away many aspects of their humanity—of what would have allowed them to stand in the light of day and call themselves whole. It wasn’t missing at birth—never a factor of their biology. They were not born without their humanity—instead, it was denied to them. In their process of becoming, they were not afforded the opportunity to be complete. This, because they could not laugh and could not smile. Because there was no Other for them to run and play alongside—no one’s hand for them to hold. Because they could never find another in whose presence they could be.

We are human, you and I—not by right of birth, but because we have made each other so.

Here’s a question. If it is as I have said—that we are removed from one another without recourse, as islands held apart by the expanse of a shimmering sea—then how can it be possible that you and I report similar experiences? If we are separated by an unbridgeable gap between our respective perceptions and how the world appears to us each, then how can it be possible that both you and I can identify commonalities in the world which we observe? That we can exist in a common space?

I think that perhaps we’ve always thought of ourselves too much as individuals. You and I put too much emphasis on our own personal experience—place too much weight on what we ourselves believe and perceive. But you and I—we have never been alone. To be sure, we are alone in our experience—in our individual conceptions of the world. However, it is also equally true that we reach out for one another—that we shape and mold each other into people. That we form connections, and we seek desperately to bridge that gap between the appearance of our worlds and the experience of the Other.

When we connect—when we form those bridges—we begin to exchange information and to construct our experiences together. We form a kind of network. No longer are we isolated individuals, for we have become part of a social cloud-consciousness, founded high up upon the pillars of faith and fantasy. We choose to trust—to believe that the experience of the Other is valid and true, and is thus in turn capable of confirming the validity of the world which appears before our own eyes.

We, as individuals, come together to form societies. We create culture and establish a code of conduct—we forge together a kind of social consciousness and social memory. In this way, each of our individual experiences, too, joins with those of others’ to form a collective faith and fantasy. This is the true nature of “reality”. It is the way in which our collective fantasy appears to us each.

Thereafter, we find that we have come upon a different kind of dualism. A dualism which says this: that we, as human beings, at once both do and do not occupy a common space of experience. We are at once alone within ourselves and our own minds—trapped and unable to break free. Yet, at the same time, we are fundamentally connected to one another; no more than simple aspects of a collective cloud-mind.

Human beings exist in this shared social space—a kind of objective world, not in the sense that it exists beyond the realm of subjective perception, but instead in that it is the world which appears collectively to us all. It is a world composed of aggregate fantasy—of subjective material given new life within a common social space. Information which the members of a given society are capable of and disposed toward seeing and believing. A social objectivity, if you would, in contrast to the metaphysical, transcendent objectivity which is so often described.

This social reality—our reality—is indisputably real. Not necessarily of its own merit—not by any kind of transcendent, metaphysical consideration—but because each of us places our faith within its veracity. Because each of us has invested our faith into the heart of that fantasy, we have made it real.

In the end, we are fundamentally and irredeemably alone. And yet, at once, it is impossible that we will ever truly be alone again. Sartre once said that the human being is a living contradiction. Granted, his intention may have been a little different, but… in this moment, I can’t think of anything more fitting to say.

7 | Happiness

I’m almost certain that I said something about happiness at the beginning of all this. In this moment, it seems to me as if that must have been so very long ago—somewhere, sometime, upon the shore of different ocean, beneath the edge of a boundless blue sky.

If you’ve been sitting there waiting to hear about happiness for all this time, then I’d like to apologize for being so long-winded. That… and I’d like to thank you for making this journey with me, whatever your thoughts on what I’ve said may be.

Here’s something that I’ve wanted to say for a very long time:

I don’t think I believe in ethics.

Right and wrong; good and evil—these are subjective constructs. They are things which you and I create—things in which we choose to invest. They are ideas fabricated; woven and spun into rough shape by means of faith and fantasy. Shifting and swaying along with the times, they adjust their form and composition to match the silhouette of the social cloud-consciousness of the day. They are a way in which the world appears. Nothing more; nothing less.

There is no such thing as good or evil—no such thing as transcendent objectivity. Or, at least, even if there is—even if it’s there, lurking somewhere just beyond our reach—then it still can’t possibly be relevant anyway.

Ethical systems of all shapes and kinds hold at their core an emphatic paragon of virtue. In the mind of every social cloud-consciousness which has ever been born upon this earth, the world has appeared in black and white. Divided between the good and the evil—the shoulds and the should-nots. Between moral rights and wrongs, and between that which is permissible and that which is forbidden.

To me, the fashion in which a cloud-consciousness enforces its ethical system inspires a deep sense of disgust. It chooses to restrain what it deems to be evil—forbidden or impermissible actions—by means of the abuse of ostracization; by slaving mankind to its own sense of guilt. Like a rabid animal or a vindictive mob, it does not engage in dialogue—instead it attacks those who would stray from its values, segregating and inflicting upon them the most deep and total isolation. It would deny them something core and essential to the very fiber of their being—to something that would serve to shape the nature of their fundamental humanity.

Ethical systems impose on individuals a true enslavement to their own guilt. They force us by the power of ever-looming shame to press ourselves into a mold—to appear as paragons of virtue within the eye of the Other. This, on pain of suffering a most cruel and lonesome fate—to seek but never again to find the Other whom we may stand beside.

So… I don’t think I believe in ethics. I think that, in this moment, I could go so far even as to say I despise it.

What do you believe in?

I believe in empathy.

A philosophy of empathy is the exercise of agency with the intention of good faith and good will.

Kindness manifests itself as rather intuitive to us as human beings. Empathy and compassion are things which we feel ingrained into our very nature. In order to seek and find the Other, we must first appear worthy of that Other’s companionship—and, as such, that appearance tends to come naturally in the demonstration of good faith and good will.

Upon closer inspection, however, it should become quickly apparent that any offering of kindness isn’t ever freely given. Instead, it’s expected that kindness be reciprocal—that the individual stands to gain in some way for offering his warmth and care. Indeed, what this philosophy demands is not necessarily so altruistic as one might be liable to expect. It holds within it at once a sense of both egoism and social responsibility—of a mutual exchange of empathy.

To practice a philosophy of empathy is to live in such a way which would allow you to exhibit good will toward not only the Other, but toward yourself as well. To live truly free, and to walk unburdened from the guilt and the shame which any system of ethics would seek to levy against you. To be kind is to find yourself finally comfortable existing underneath your own skin—

Where you might find yourself finally at peace even in the depths of your own mind.

Kindness will set you free. Be kind to others, and you may yet learn what it is to be kind to yourself. Do not ask yourself what you should do to act rightly—whether by moral or ethical system, or in accordance with any law or social decree. Instead, first ask yourself what it must be like to find yourself it that Other’s place. And then… be kind to yourself.

Perhaps, in the end, a philosophy of empathy is not so different from the core tenets which an ethical system may hold at its foundation. Perhaps the difference lies only in the respect with which you regard that system—in the attitude which you take in consideration of its nature. Perhaps to live by a philosophy of kindness is simply to hold in mind the understanding that ethical systems are not absolute, objective truths. That the laws and mores and customs which govern man are created by man and mankind—that the things which we believe to be truth are spawned sheerly from the social cloud.

Perhaps it is as Sartre and Beauvoir have said—that the gaze of the Other fixes us in facticity; within a common world. That in order for us—for you and I—to be truly free, the Other must too be afforded that same freedom. That empathy must be extended to the Other so that they may in turn bear witness to you—to everything that you are, and everything that you will be.

Happiness, itself, must be the most valuable commodity in all the world. It’s what everyone wants—what everyone seeks. Yet even still today, none have ever discovered where or how it may reliably be obtained.

Ask yourself this question:

Can we grow happiness upon the soil? Can we mine it from the earth?

The answer is no… obviously. But, if we could…

Wouldn’t we?

If, one day, someone struck the earth with the bit of a drill and found that happiness welled forth from the ground, humanity would suck that tap dry in an instant, drinking it down in a euphoric craze. Then, we would go looking for more and more, and we would never seek anything else again. We are hungry for it—voracious, and insatiable.

Everybody’s looking for happiness. Whether they realize it or not, everybody’s trying to feel good—to be happy. Some search for it through creature comforts. Others through the exercise of their base instincts. Some try to find it in substance abuse. Others try to invest themselves in a project of social duty.

There isn’t a right or wrong way—a good or bad way—to look for lasting happiness. I won’t pretend to know the best way to go about finding it, and I won’t pretend that I can teach that method to you. After all, I am the only me, and you are the only you. We are each ever alone—together in our isolation.

The world which you see is nothing like mine.

So, I’m sorry to say that I can’t answer your question. It isn’t that I haven’t been able to find an answer—rather, it’s that I can only ever answer that question for myself. My answer, after all, is only ever my own. The best I can do for you is to tell you about me—to teach you how I can be happy. And maybe—just maybe—that might help you to find your own way. To live in a fashion which can convince you in your own mind that you really are truly happy.

I am genial. I try to afford the Other so much respect as I can muster. I will sit and listen with the patience of a resting boulder to whomever decides that they’d like me to hear their story.

I am blunt. I tend not to lie—not out of any kind of moral-ethical conviction, but instead out of sheer convenience. After all, I’m not much of a spider. For me, it’s always seemed quite a hassle to maintain a web of lies.

In truth, I am much more like a tortoise. I take things slow, and I like to keep them simple. One step, one idea—one project at a time. My shell is hard and sturdy. My head is angled low, my eyes trained on the ground before me. But oftentimes, I’ll find myself climbing my way up a hill just so that I can catch a glimpse of the clouds and the sky.

I try my very best to be unequivocally kind, and it makes me a little sad—and, at times, really quite angry—when I see that people refuse to even attempt to understand another person’s side.

Kindness has set me free—kindness toward others, and kindness toward myself. My head is level. The undying tempest which once swirled in my mind has long-since fallen silent. A philosophy of empathy has put me in a place where the troubles and strife of living tend to wash right off my back. In the spirit of Camus, it’s given me freedom from hope—from my once-deep concern for the black-and-white world of ethical systems, and of being judged right or wrong in anyone else’s eyes. It’s allowed me to invest in Sartrian projects with this strange new vigor that I could never muster before.

Do the things you want to do. Hold kindness in your heart. Plant your faith firm within your fantasy.

I believe in empathy; in kindness, as I imagine it to be.

What do you believe?