On Theory, Knowledge, and the Meaning of Metaphysics

a Modern Empiricist’s Response to the Hypothesis of a Priori Knowledge

1 | On Metaphysical Knowledge

μετα | meta: after

φυσικά | physika: physics

Metaphysics: after the physics

If so desired, theoretical knowledge may be referred to instead as metaphysical—after all, that is the original meaning of the word.

If, however, we deem it fit to use these two terms in this way (that is, to define metaphysical knowledge as theoretical knowledge), then we must acknowledge that theoretical knowledge is necessarily knowledge which is created.

Theory is created; first-conceived-of in the mind of a thinker using premises formulated from data which must in turn have been drawn from prior knowledge—either the personal experience of a given person, or from socially-inherited knowledge which has been conveyed to that person by someone else. In other words:

Meta-physics must follow physics—and any theory concerning the nature of the world may only be formulated after an observation of the nature of that world has been conducted. To attempt, after all, to theorize before gathering any input-data… would be like an infant trying to do simple addition before having learned any numbers.

By its own, very simple definition:

Metaphysics is what comes after.

2 | On a Priori Knowledge

A | a: from

PRIUS | prius: earlier times

a Priori: from before

a Priori knowledge can be defined as theoretical knowledge which comes from before—that is, from before observation. Therefore, a priori knowledge cannot coherently constitute knowledge because it presupposes the existence of inherently or innately known axiomatic data which can only be assumed to be known by means of the intuition of given human minds—and, therefore, cannot be assigned truth value (or, in other words, is assumed true but is actually impossible to either confirm or deny).

a Priori knowledge—theoretical knowledge which precedes all observation—by definition can never have been witnessed. Thus, it cannot have been obtained by means of perception, nor can it be a logical derivative of that perception… and, therefore, can bear no plausible relation to a physical, observable world.

If we can thus acknowledge that the above endorsement of the “a priori” form of theory-from-before is neither coherent nor convincing, then the form of theory which can remain is that of the “meta-physical”—that is, of theory which comes after. After all, all knowledge which can be demonstrably known (at least, to the best of our ability) is first only that which can be directly observed and experienced… and then, thereafter, the theoretical knowledge which can be derived from it, and be back-tested, proven-out, and therefore confirmed (to a reasonable degree of certainty) within the the environment of the physical, tangible world which we inhabit.

Theory is knowledge which has been created—and thus, must have been created by someone. Theoretical knowledge cannot be constituted in the absence of data—and the only data to which we can convincingly claim to have access is either our own, personal, empirical observations and the theory which we derive from them… or the information which has been reported to us as the experience of other people, and the theory which they have derived from it.

In other, simpler terms:

Theory is the stories which we tell ourselves… and the stories which are told to us by other people.

3 | The Stories We Tell

A theory is a story which is told: a hypothesis which details information which is surmised to be truth, and a narrative concerning a reality of the world as-once-experienced from someone’s perspective. Thus, theory can only be coherently claimed to be an empirical derivative—knowledge which has been derived from the collective experience of our forebearers.

The common Kantian assertion of the reconciliation of the analytic with the empirical through the advent of the synthetic is thus rendered also incoherent, for—regardless of whether some a priori knowledge is thought to be either half- or wholly-unempirical—theory can only be rationally proposed as belonging to the meta-physical kind: as following the experience of the physical world.

Let’s tell a story of our own.

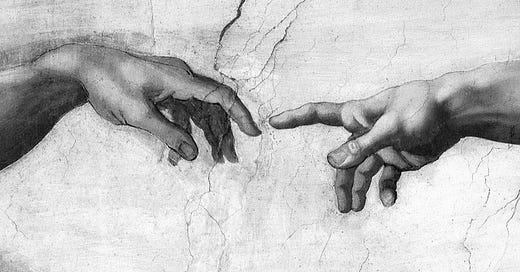

Imagine here primus homo—the first man—who finds himself suddenly upon the earth, completely and utterly alone. He opens his eyes for the very first time, and finds that he experiences sensations—that he sees, hears, and smells all the features of a brand new world. He reaches out to touch—to feel, and grasps at rocks and trees. He licks the dirt, and—thus finding it rather unpleasant—cleans his tongue and elects to not do it again. He moves his limbs and finds, after a while, that if he moves them in a certain way, he can propel himself across the ground, beginning to crawl as creatures do. He explores for a while, and then looks up, and is greeted with the sight of some strange, colorful orbs suspended from the branches overhead. He reaches out to grasp them—finding them to be both soft and firm, and smelling of an interesting aroma. He takes a bite, and finds it sweet—that it feels good to chew, and to swallow and eat.

This is primus homo—the child who enters the world tabula rasa—and who knows because he learns; because he moves to observe and experience the world, and thereby acquires knowledge of it. After all, in a feral world in which he finds himself completely and utterly alone, from what other source could he hope to obtain knowledge than through his own investigation?

Now imagine here secundus homo—the second man—whom our first man stumbles upon. The second man sits upon the earth, still grasping at rocks and trees. The first man, delighted to meet another like himself, taps the second man’s arms and legs, and then begins to move his own body back and forth. Having thus taught the second man how to crawl across the ground, the first man gestures in a vague direction, motioning for the second man to come. Arriving at the place where colorful orbs hang from trees, the first man plucks one and takes a bite, then hands the fruit to the second man. In this way, the second man thus also learns to eat through following the first man’s example.

A theory is a story which is told: a story about how to crawl on the ground, or how to eat the fruit from trees. A theory is an empirical derivative—a story which describes knowledge gathered from prior experience of the physical world, and which allows those who come after to benefit from the observations of those who came before.

…

One might be tempted here to attempt to make an argument towards biological determinism, to which I would say the following:

Genetic or biological predisposition does not give rise to anything which constitutes knowledge. Knowledge, after all, is what is known—and thus, moreover, what has been learned. One does not, for example first possess an innate knowledge of how to breathe. Instead, one simply does just breathe.

From the fact that one, as a human being, first does breathe, we may then draw an empirical understanding of what it is to breathe—and then, thereafter, make the observation that it is also possible for us to come to know how to control this breathing. We would not say, after all, that we possess innate knowledge of how to beat our hearts—instead, only that we know through our own empirical observations that our hearts do beat.

4 | The Stories We’re Told

History is a story which is told—literally, a story about things which have happened before; of events which were witnessed by people in the past, and thereafter committed to social memory.

Math and logic are stories which are told—a system of reasoning created by man which makes use of theoretical forms in attempts to describe a state of the world, and which are in-turn described by and derived from the prior experience of other people; those who observed before us.

Language itself—the fundamental medium of shared experience—is a story which is told; an arbitrary system of communication which can be acquired only through the experience of it, and is demonstrably inaccessible to any given person who has never observed its usage.

Thus, we can see that there are in reality only two ways in which knowledge can be sourced:

1. Through direct observation and discovery, and by acquiring and confirming that knowledge for ourselves, or;

2. Through indirect observation, and acquiring that knowledge from someone else who claims to have discovered and confirmed it for themselves.

Both methods necessarily claim empirical basis—the difference lies only in the who it is that serves as the source of that claim.